-By LeN Colombo Correspondent

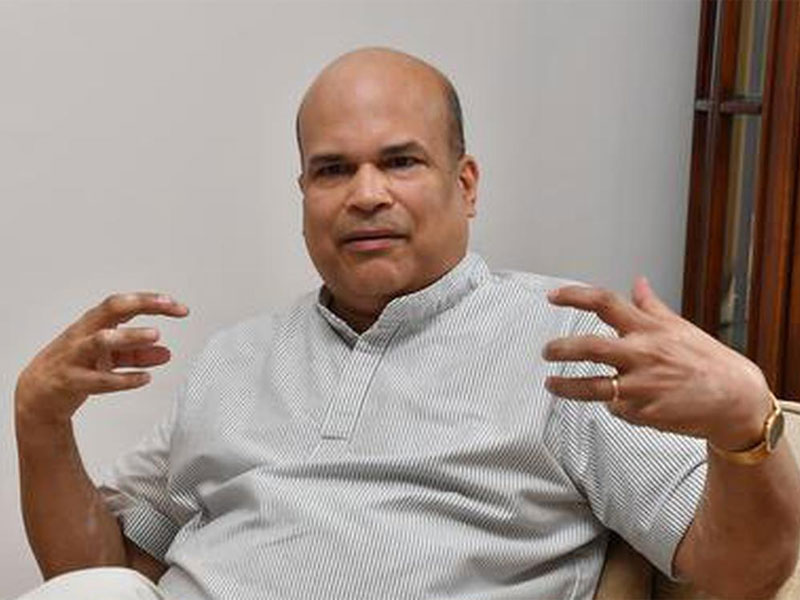

(Lanka-e-News -23.April.2025, 11.30 PM) In the annals of Sri Lankan politics, the name Milinda Moragoda occasionally surfaces like an old yacht—rusting quietly in the shadow of the port he once gave away. Now, two decades later, the sea breeze carries back the unmistakable stench of scandal. The ghost ship of Lanka Marine Services Limited (LMSL) is bobbing back to the surface—and this time, its captain might not sail away so smoothly.

The current government, led by the National People's Power (NPP), is reopening the books on the 2002 LMSL privatisation deal, in which 8.5 acres of prime Colombo harbour land was handed over, not unlike a wedding dowry, to John Keells Holdings (JKH). The twist? This wasn’t just any corporate merger—it was a transaction wrapped in family ties, submerged in corruption, and lubricated by privilege.

The man at the helm: Milinda Moragoda. The charge? Abuse of public property, betrayal of public trust, and enough nepotism to make even a banana republic blush.

To understand the scandal is to first appreciate the land. The LMSL plot, nestled in the beating heart of the Colombo Port, was no forgotten backwater. It was strategic, lucrative, and state-owned—until it wasn't.

In 2002, the land was transferred from the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) to LMSL, which was then privatized. The buyer: John Keells Holdings, Sri Lanka's biggest blue-chip conglomerate. The seller: the state, or more precisely, a few select men acting with the finesse of used-car dealers.

The Supreme Court, in a landmark judgment, found the sale to be illegal. It named P.B. Jayasundara, then Chairman of the Public Enterprise Reform Commission (PERC), and Susantha Ratnayake of JKH, as having acted with “dishonest intent.” But while Jayasundara was dragged across the legal coals and Ratnayake’s halo tilted, the real fire was aimed at Moragoda, then the Minister under whose watch the transaction was blessed with holy water.

And now, that fire is being reignited.

At the time, Moragoda's move was Shakespearean. With the Bribery Commission sniffing at his heels, the former United National Party (UNP) minister suddenly developed an affection for the ruling party. Like a rat on a floating banana, he scuttled over to Mahinda Rajapaksa’s side. Investigation files, curiously, went cold.

The result? Sri Lanka’s most damning privatisation scandal was placed on a political ventilator—one that conveniently unplugged itself.

Now, the ventilator is humming back to life.

In early April, the NPP government announced a reopening of the LMSL case. Two new investigations are underway—one by the reformed Bribery Commission and another by a parliamentary oversight panel. “Public land cannot be used as family heirlooms,” said one MP dryly, adding that “this isn’t a feudal state, even if some politicians act like hereditary dukes.”

Critics have long pointed out that this wasn’t just crony capitalism—it was family capitalism.

LMSL’s new owners, John Keells, were not exactly strangers to Moragoda. His sister is married to Krishan Balendra, current chairman of JKH. A man, notably, whose rise has baffled even high-society Tamils due to his ‘low caste’ background—an irony lost on no one given the ultra-Sinhala-nationalist pedigree of the Moragoda family.

Their grandfather, N.U. Jayawardena, was a known right-wing economist who considered the economy as a sacred preserve of the Sinhala elite. He founded Sampath Bank to create a Sinhala merchant class. Yet his granddaughter’s union with a Tamil of "untouchable" status has turned that vision upside down. It would be farcical, if not so poetically just.

The result? A scandal embroidered in layers of hypocrisy, caste, ethnicity, and post-colonial capitalism—served with a side of curry and elitism.

According to the 2008 COPE (Committee on Public Enterprises) report, the LMSL sale resulted in a staggering Rs. 1.7 billion loss to the Sri Lankan government. That’s nearly USD 5 million at 2002 rates—enough to fund an entire fleet of coastal guard vessels or at least one properly functioning public hospital.

COPE was unequivocal in its condemnation. “By his actions,” the report read, “Mr. Moragoda incurred a massive loss to the State.” But like all good Shakespearean villains, Moragoda vanished from the stage before the curtain fell.

The Bribery Commission's investigation too, conveniently evaporated once Moragoda was ensconced within the ruling alliance. His stint as Sri Lanka’s Ambassador to the United States further provided him the diplomatic immunity that shielded him from prosecution. It was a golden parachute, stitched with threads of immunity, impunity, and irony.

Now, with a new sheriff in town—one with a stated mandate for transparency—the plot has returned to the headlines. The NPP’s internal task force on economic crimes has unearthed fresh documentation allegedly proving that the land was transferred at a fraction of its market value, and that prior assessments were manipulated.

“This was daylight robbery,” an official said. “It was a hostile takeover dressed as reform.”

The Bribery Commission is also seeking legal advice on whether the old charges can be revived under the Public Property Act. Under this law, even officials who "failed to act" to prevent loss to the State can be prosecuted.

Moragoda’s defence, according to sources close to him, hinges on procedural ambiguity and the argument that PERC was acting “on expert advice.” But the NPP appears determined to test whether that “expert advice” was paid for—in cash or in wedding rings.

What’s most galling to the public is how systemic and shameless the whole affair was. This wasn’t a slip-up or oversight. It was a slow, deliberate gutting of national assets for personal and political gain.

“It’s not just about one man,” says Dr. Vishaka Amarasekara, a governance researcher. “It’s about a culture of impunity that spans decades, families, and boardrooms.”

The LMSL sale is now being held up as a textbook case of why Sri Lanka fell into a debt trap—selling off national assets to pay off loans, rewarding the powerful, and leaving the public with potholes and promises.

Some analysts note that this investigation may also have political subtext. By going after Moragoda, the NPP might be sending a not-so-subtle message to remnants of the old guard, particularly those aligned with Rajapaksa-era politics. After all, Moragoda was one of the few crossover ministers who enjoyed uninterrupted political favour under both UNP and SLPP governments.

That he might finally be called to account—after escaping the hangman’s noose for so long—suggests the NPP might be sharpening its blades for a broader political clean-up.

As the inquiry gains traction, the people of Sri Lanka are watching. This time, the political climate is different. Social media has replaced Sunday sermons, and civil society is less inclined to turn a blind eye. The JKH empire, for its part, remains silent. Krishan Balendra, whose ties to Moragoda are now being openly discussed in Colombo drawing rooms, has not made any public statement.

Meanwhile, opposition politicians smell blood. “Moragoda should be tried in a court of law, not honoured in diplomatic lounges,” said one JVP MP.

If the government proceeds with criminal charges, it could set a precedent for other controversial privatisations from the 1990s and 2000s. From the Hilton Hotel to SriLankan Airlines, the graveyard is crowded.

But LMSL remains the crown jewel—the scandal that was too big, too blatant, and too intricately rigged to be forgotten.

In the end, Milinda Moragoda may not go to jail. He may not even be indicted. Sri Lanka’s justice system, after all, has a long memory but short legs. But what’s undeniable is this: the LMSL scandal is no longer buried.

It is back—reopened, re-lit, and roaring into the national consciousness like a ship that never really sank.

And Milinda Moragoda, once the golden boy of neoliberal reform, may find himself explaining to a judge, and not just a dinner guest, why the country lost billions while he gained a brother-in-law.

-By LeN Colombo Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-04-23 18:28:43)

Leave a Reply