-By LeN Political Editor

(Lanka-e-News -08.May.2025, 11.15 PM) In what is being hailed as a seismic shift in Sri Lanka’s political landscape, the National People's Power (NPP) has won a stunning 267 local government bodies in the long-delayed local authority elections held on May 6. With 3,926 members elected across the country, and 43.26% of the national vote, the leftist-populist coalition has now firmly extended its dominance from the presidential palace to the smallest pradeshiya sabhas — Sri Lanka’s grassroots institutions of governance.

This marks the third sweeping electoral victory for the NPP in less than two years — following its surprise presidential win and subsequent parliamentary majority. Now, the red flag of the JVP-led alliance flies not only over the national government, but across town councils, municipal authorities, and village-level bodies from Galle to Gampaha.

While voter turnout was modest, the political message could not be clearer. The old order, once held aloft by dynastic parties and patronage machines, is collapsing. A new one — promising discipline, equity, and export-led growth — is very much in charge.

These local elections were originally scheduled to be held in 2023 but were postponed multiple times, officially due to financial constraints and logistical challenges. Unofficially, critics say, the delay was a ploy by the then-incumbent UNP-SLPP alliance to postpone what they feared would be a humiliating defeat. They were not wrong.

The NPP’s decisive performance reveals the depth of its grassroots appeal and organisational strength. With only a fraction of the resources traditionally marshalled by the two major parties — the United National Party (UNP) and the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) — the NPP fielded candidates in almost every ward and constituency, relying on volunteer networks, social media mobilisation, and policy-driven campaigning.

In stark contrast, the SLPP, once helmed by Mahinda Rajapaksa and dominant across the South, managed a paltry 9.17% of the vote and secured no control over any local body. Its 742 elected members will sit in opposition — if at all. The UNP, which once prided itself on its stronghold over the Colombo Municipal Council for more than 50 years, was decimated. Its national vote share plummeted to just 4.69%, with only 381 members elected.

Even the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), which had emerged as the principal opposition force during the Rajapaksa downfall, failed to make serious gains. Despite winning 1,767 seats, it managed to wrest control of only 14 local bodies, with just 21.69% of the popular vote.

It was the NPP — youthful, tech-savvy, and ideologically grounded — that captured the public mood.

“This is more than a victory,” declared NPP leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake at a jubilant press conference in Colombo. “This is a confirmation that our people want transformation — not just in Parliament, but in their own streets, towns, and villages.”

For Dissanayake, who came to power on a wave of anti-corruption anger and post-crisis fervour, the local government victory offers both a validation and a warning. The public expects delivery — not slogans. The movement’s ambitious social and economic reforms, including its “Village First” development programme, will now be judged in the real-world performance of local councils.

With local authorities in hand, the NPP can now implement its development portfolio from the ground up. Their flagship policies — urban waste-to-energy projects, village-level food cooperatives, smallholder agricultural reforms, and public health extension programmes — all require coordination with municipal governments.

Where the Rajapaksas once ran these institutions as patronage hubs, the NPP promises transparency and accountability. Local councillors are being trained not just in administration but in public service ethics and procurement law.

The International Monetary Fund, which has backed Sri Lanka’s economic recovery since the debt default in 2022, has reportedly welcomed the NPP’s electoral consolidation — albeit cautiously.

“We are encouraged to see stability and public support for a reform-oriented government,” an IMF spokesperson told The Times on condition of anonymity. “The challenge now is delivery — especially on structural reforms that require broad local buy-in.”

Under the NPP, Sri Lanka has committed to a radical transformation of its economy from one reliant on debt and consumption, to one driven by exports, innovation, and value addition. The early signs are promising: export revenues have climbed 17% year-on-year, the rupee has stabilised, and foreign direct investment has begun trickling back.

But economists warn that national targets must be matched by subnational implementation.

“You can’t just announce reform in Colombo and expect it to succeed,” says Prof. Deepani Perera, an economist at the University of Peradeniya. “You need competent local authorities to enforce zoning rules, manage public infrastructure, and support small business ecosystems. The NPP now controls these levers. They have no excuse.”

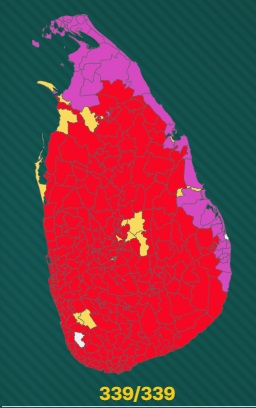

Perhaps the most revealing aspect of the NPP’s performance is its geographical spread. Without significant backing from the Northern and Eastern provinces — where Tamil and Muslim parties remain dominant — the party still managed to command the majority in most local authorities across the South, West, and Central provinces.

This leaves a conspicuous political gap.

In the North and East, parties like the Ilankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK) and various Muslim alliances still hold sway. They collectively garnered around 17.47% of the national vote and 1,676 elected members — enough to control key urban councils in Jaffna, Batticaloa, and Trincomalee.

The NPP has made overtures to these parties in recent months, promising devolution, post-war reconciliation, and equal access to development. But the trust deficit remains.

“The Tamil people want justice and self-respect, not just development,” says M. Sivalingam, a senior councillor from ITAK. “We’re watching to see if the NPP is genuinely different, or just a more disciplined version of the Sinhala state.”

To govern the whole island — and not just the South — the NPP will need to bridge this divide.

With municipal control comes responsibility — and visibility. Local councillors, once obscure intermediaries, will now be scrutinised for potholes, playgrounds, and garbage collection. The NPP’s war on corruption, which it waged with gusto in the national parliament, must now trickle down.

Already, the Ministry of Provincial Councils and Local Government has issued new circulars to NPP-controlled bodies mandating quarterly financial disclosures, e-procurement, and citizen budget consultations.

But the real test will be cultural.

“People are used to calling their local councillor for a job, a school transfer, or even a wedding tent,” says Mahesha Silva, a senior bureaucrat. “That’s going to change. Or at least, that’s what the NPP says. Whether they can change that mindset remains to be seen.”

For now, the mood among NPP supporters is jubilant. Crowds in cities like Kurunegala, Kandy, and Matara danced in the streets. Social media, especially TikTok and WhatsApp groups, exploded with celebratory memes and mock funerals for the SLPP.

In Colombo, the image of a lone UNP flag flying over an empty municipal building — once the bastion of party aristocrats — became a viral symbol of decline.

Meanwhile, the Rajapaksa family is said to be in disarray. Sources close to the clan report growing tensions between Mahinda and Basil Rajapaksa, with speculation of an internal coup within the SLPP to install younger leadership. But with no local authority under their control, and a discredited legacy behind them, the party’s road back to power looks forbiddingly long.

What the NPP now possesses is unprecedented in modern Sri Lankan history: a simultaneous mandate at the presidential, parliamentary, and local levels. Such consolidation is rare — and risky.

In democracies where one party holds all levers, the dangers of arrogance, groupthink, and inertia loom large. But for a movement forged in opposition and driven by ideology, the NPP sees this as a moment to prove that politics can be reimagined.

“We're not here to fill chairs or parade power,” said a young NPP councillor from Anuradhapura. “We’re here to show that politics is about serving people — not stealing from them.”

If they succeed, it could herald a long-term political realignment — not just in Sri Lanka, but as a case study in the post-crisis revival of democracy.

If they fail, they may discover that toppling the old order is far easier than building a new one.

-By LeN Political Editor

---------------------------

by (2025-05-08 17:55:16)

Leave a Reply