-By A Special Correspondent

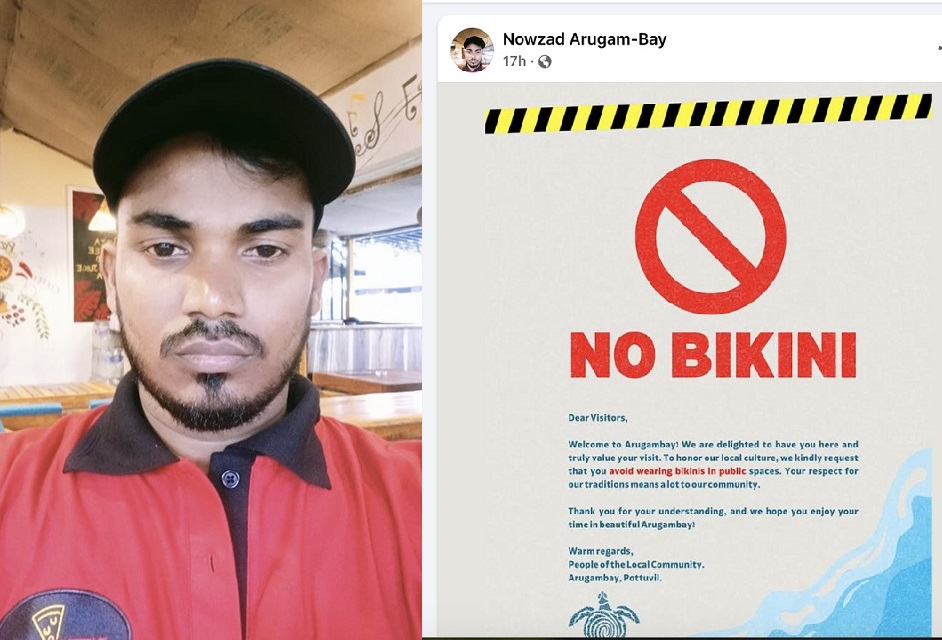

(Lanka-e-News -25.May.2025, 11.30 PM) It began, as many absurdities do in the modern age, with a poster. Plastered across Instagram like a digital fatwa, the sign in question declared—loudly, officiously, and without a whiff of irony—that walking around Arugam Bay in a bikini was now strictly prohibited. Issued not by the Sri Lankan Tourism Authority, nor the local police, but rather a certain digital crusader by the name of “Naushad – Arugam Bay,” whose 5,400 social media followers apparently now outrank the Constitution.

Naushad’s diktat has gone viral—spreading across local chat groups and beach café WhatsApps faster than a tourist with an unfortunate bout of food poisoning. The poster features no legal citation, no government seal, not even a polite suggestion. Just an unambiguous order: no bikinis in Arugam Bay. The town, it appears, is under new management—and its name is Wahhabism 2.0.

This development might be laughable were it not so ominous. Sri Lanka’s tourism industry is emerging from the trauma of the pandemic and decades of economic mismanagement. With the southern and western coastal towns entering their annual monsoonal slumber, the Eastern Province—particularly Arugam Bay—is now the primary engine of tourist revenue for the next six months. And yet, into this fragile ecosystem has parachuted a cultural edict seemingly lifted straight out of Riyadh circa 1987.

One is tempted to ask: is this a misguided attempt at enforcing “local values”? Or is it something darker—a creeping extension of the same ideological dogma that turned Sri Lanka’s beaches into battlegrounds in April 2019?

The echoes are disturbing. In April 2019, Wahhabi extremists detonated themselves in Sri Lanka’s most prestigious five-star hotels and Christian churches, killing over 270 innocent people—including dozens of foreign tourists. The attacks dealt a devastating blow to the nation’s tourism sector, which still hasn’t fully recovered.

Now, in 2025, we find ourselves confronted by a softer, quieter form of extremism—not with bombs, but with posters and hashtags. It is, as one tourism operator in Pottuvil quipped, “a cultural suicide bombing.”

If bikinis are now banned in Arugam Bay, one must ask: What next? Will shorts be outlawed? Will female tourists be asked to cover their hair before sipping on a mojito? Will sandcastles need planning permission from the local mosque committee?

Let us be clear: Arugam Bay is not Kandahar. It is a global surf destination, where Australians come to drink beer and fall off longboards, Germans arrive to meditate topless, and the French mostly smoke. It has thrived not because of ideology, but because it was one of the few places in postwar Sri Lanka where tolerance and commerce could coexist. Until now.

This bikini ban isn’t an isolated act of digital puritanism. It’s part of a growing trend of self-imposed moral policing stretching across the Eastern Province—from Batticaloa to Kalmunai to the surfer havens of Arugam Bay.

Already, bans on cigarette sales and public alcohol consumption are in place in several predominantly Muslim towns. In some areas, music has been all but silenced, and women’s dress codes informally enforced through a mixture of peer pressure and poorly disguised threats.

The state’s silence has been deafening. Successive governments—both blue and red—have largely turned a blind eye to the steady encroachment of Wahhabi norms in the east, for fear of offending “religious sensitivities.” But at what cost?

One might recall that Zaharan Hashim—the moustachioed mastermind of the Easter bombings—cut his teeth preaching in these same regions. In fact, before founding his own death cult, Zaharan was booted from a local mosque for watching porn. This writer can’t help but wonder: is Naushad Arugam Bay a spiritual cousin of Zaharan? A Wahhabi wellness influencer?

Either way, the danger is the same. Cultural radicalism, even when delivered via Canva and TikTok, is radicalism nonetheless.

This incident presents a three-headed danger, each more politically inconvenient than the next.

First, it provides a golden cudgel for Sinhala-Buddhist extremists, who are already crafting anti-Muslim narratives with the dexterity of a Colombo tailor during wedding season. For them, the Arugam Bay “bikini ban” will be paraded as proof of creeping Sharia—a justification for their own bigotry, now conveniently wrapped in Lycra.

Second, it hands a Molotov cocktail to the government’s critics. The administration of President Anura Kumara Dissanayake—despite its progressive branding—is now facing questions about whether it truly has a handle on extremism, or whether it’s simply too distracted nationalizing supermarkets to notice cultural implosions on the coastline.

With tourism income hanging by a sunburnt thread, any perception that Sri Lanka is turning into a conservative theocracy could sink the industry for another high season. Protesters are already sharpening their slogans.

Third, and most dangerously, it enables internal Wahhabi consolidation. What begins with a poster can escalate to informal dress codes, followed by calls for gender-segregated beaches, mosque-controlled alcohol bans, and a de facto moral police. In some areas, it already has.

The Sri Lankan state, in typical fashion, appears caught in a permanent game of cricket with itself—batting for religious freedom while fielding for economic survival. But this is not a situation that calls for balance. It calls for a spine.

Regulatory authorities must take a clear and public stand against all forms of unofficial moral legislation. If Naushad wants to issue public orders, he should first win a parliamentary seat—or at least a municipal election. Until then, he must take his modesty mandates and peddle them elsewhere.

This also presents a vital opportunity for moderate Muslim voices to stand up and declare: “Not in our name.” If Wahhabism is left unchecked in the east, it will soon dominate the social fabric, erasing centuries of syncretic Islamic tradition in favor of imported Saudi rigidity.

Sri Lanka must now decide what kind of tourism destination it wants to be. Is it a place where travellers can sip arrack under the stars, or a place where they are fined for showing their shoulders? Are we trying to revive the economy—or perform cultural experiments on unsuspecting Australians?

The government should remember: tourists don’t buy plane tickets to be told what not to wear. That service is already available in Iran.

It’s time to act. Silence is no longer neutrality. It is complicity.

Perhaps Naushad of Arugam Bay should consider a more productive hobby—like surfing, or climate activism, or stand-up comedy. At the very least, someone could introduce him to the Sri Lankan Constitution, where he’ll find that citizens (and tourists) are still legally entitled to wear whatever they bloody well want.

If he remains adamant, we suggest he form his own coastal caliphate—perhaps on an uninhabited island, where dress codes and decency laws can be enforced with total zeal and zero tourists.

As for the rest of us, let Arugam Bay remain what it always was meant to be: a chaotic, beautiful, and slightly sunburnt collision of cultures—where bikinis are welcome, burqas are respected, and the only true law is the tide.

-By A Special Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-05-25 20:49:54)

Leave a Reply