From rebellion to rule, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) celebrates 60 years in power and purpose

(Lanka-e-News -28.May.2025, 11.20 PM) London – Beneath the modest rafters of Perivale Primary School’s lower hall in West London, a remarkable anniversary will unfold on May 31st. Buses will offload the faithful—immigrant workers, students, intellectuals, even retirees in red scarves—and the London chapter of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) will mark a milestone unimaginable decades ago: 60 years of political life, and this time, in power.

It is a moment not merely of celebration but of global resonance. A party once hunted, exiled, vilified, and massacred now presides over Sri Lanka’s government. With the National People’s Power (NPP) coalition at its side, the JVP holds the Presidency, commands a parliamentary majority, and governs a lion’s share of local councils.

“Invincible,” their London invitation boasts. And for once, hyperbole takes a back seat to history.

To grasp what makes the JVP's 60th anniversary extraordinary, one must first consider where it began.

Founded in 1965 by the firebrand Rohana Wijeweera, the JVP was born in rejection—of colonial legacies, bourgeois Marxism, and the crumbling compromises of the traditional left. The Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) had aligned with the SLFP. The Communist Party of Sri Lanka (CPSL), including Wijeweera’s own father, followed suit. But the youth—students, labourers, farmers—sought purer flames. The JVP offered them fire.

By 1971, the party’s ideological defiance had turned revolutionary. Inspired by Che Guevara, Lenin, and Mao, Wijeweera led a nationwide insurrection. It was brutally crushed. Thousands were jailed. The myth of the “Marxist bogeyman” had a new face.

Yet the JVP survived. And in 1987–89, it resurfaced—angrier, more sophisticated, more lethal. The second insurrection, triggered by Indian military intervention and worsening economic inequities, descended into mayhem. Death squads roamed the streets. State repression hit medieval lows. Over 60,000, mostly youth, were killed. Wijeweera himself was executed in custody.

Any other movement might have perished. But the JVP proved what few political organisms can: ideological immortality.

The JVP’s post-1989 years were not glorious. They were gritty.

Emerging from the underground in the mid-1990s, the party reinvented itself. Gone were the guns; in came the manifestos. A parliamentary path was chosen. The JVP ran for elections, won seats, and stunned many with its newfound commitment to electoral democracy. In the 2004 general election, they secured 39 seats—an unprecedented feat for a party with such a militant past.

Yet the flirtation with the Rajapaksa regime proved poisonous. Their decision to support Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2005 backfired when Sinhala nationalism overtook class politics. Internal divisions festered. By the late 2000s, the JVP was drifting—until the birth of the National People's Power (NPP) coalition rekindled the flame.

The NPP, a coalition of academics, activists, professionals, and progressives, infused the JVP with broader appeal. No longer merely a revolutionary vanguard, it became a credible national alternative. And in 2024, against all odds, it triumphed.

Today, the JVP-NPP government presides over a nation that has long flirted with collapse. Sri Lanka’s post-pandemic economy was crippled by debt, corruption, and geopolitical whiplash. The Rajapaksa years, laden with overses loans and dynastic arrogance, left a trail of bankruptcy and betrayal.

Into this chaos stepped a party once condemned to the margins. The JVP promised—and delivered—something rare in Sri Lankan politics: discipline. Ministers refused luxury vehicles. Corruption probes became real. Public servants were vetted. The old culture of entitlement was challenged by a new ethos of austerity.

And the people responded. The President—once a teargas-dodging Marxist—is now a statesman navigating IMF deals and digital reforms. Parliamentarians, many in their 30s and 40s, debate not dynasty, but data. For once, Colombo’s political class looks more like its population.

This Saturday’s event in London is more than a nostalgic commemoration. It is a moment of global alignment.

The Sri Lankan diaspora in Britain—once a fractured, wary group—now finds common cause in a government it can believe in. JVP’s UK Committee, a motley of former exiles, trade unionists, and university lecturers, has grown increasingly visible.

“This is not about flags or banners,” says Perera, a London-based organiser and one-time political prisoner. “It’s about dignity. For the first time, we have a government in Sri Lanka that doesn’t make us cringe.”

In Perivale, speeches will be made in Sinhala and Tamil. A Tamil member of the NPP will address the crowd, a sign of the coalition’s cross-ethnic credibility. JVP today does what few southern parties dare: speak the language of reconciliation without pandering.

There will also be a tribute to the martyrs—those who fell in ‘71 and ‘89, whose portraits still hang in London’s JVP- members living rooms. “This victory is for them too,” says Kumari S., a British nurse whose brother was abducted in 1989.

For all its victories, the JVP remains a controversial force. Detractors, particularly among older generations, recall the insurrections with fear. Human rights groups still demand full reckoning with the abuses of the 1980s. The party’s critics abroad, especially in right-leaning Tamil diaspora circles, remain wary.

There are also doubts about its ability to manage complex economic systems. Ideological rigidity, some argue, could hinder foreign investment. And then there’s the question of India: the JVP has historically been suspicious of both Indian and Western capital. Its challenge will be walking the tightrope between sovereignty and solvency.

Yet the new generation of JVP leaders are not dogmatists. Many are engineers, economists, lawyers. The PresidentAnura Kumara- himself is known to quote both Marx and Adam Smith. It is pragmatism, not purism, that defines the new era.

When Rohana Wijeweera began his lecture series in the late 1960s—famously scribbled on blackboards under mango trees—he could scarcely have imagined that his party would one day run the country, let alone celebrate, ts 60th Annivessary in suburban London.

But this is the nature of revolutions. They begin in obscurity, are born in fire, stumble through ashes, and—if they survive—emerge not just transformed, but transforming.

For the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, 60 years is more than a birthday. It is a vindication of sacrifice, a rewriting of destiny, and a reminder to the world that in politics, as in history, the last laugh often belongs to the long marchers.

And so, in Perivale this weekend, a handful of Sri Lankans will gather, not to mourn or mythologise, but to affirm: yes, revolutionaries can govern—and do so, not in exile, but in office.

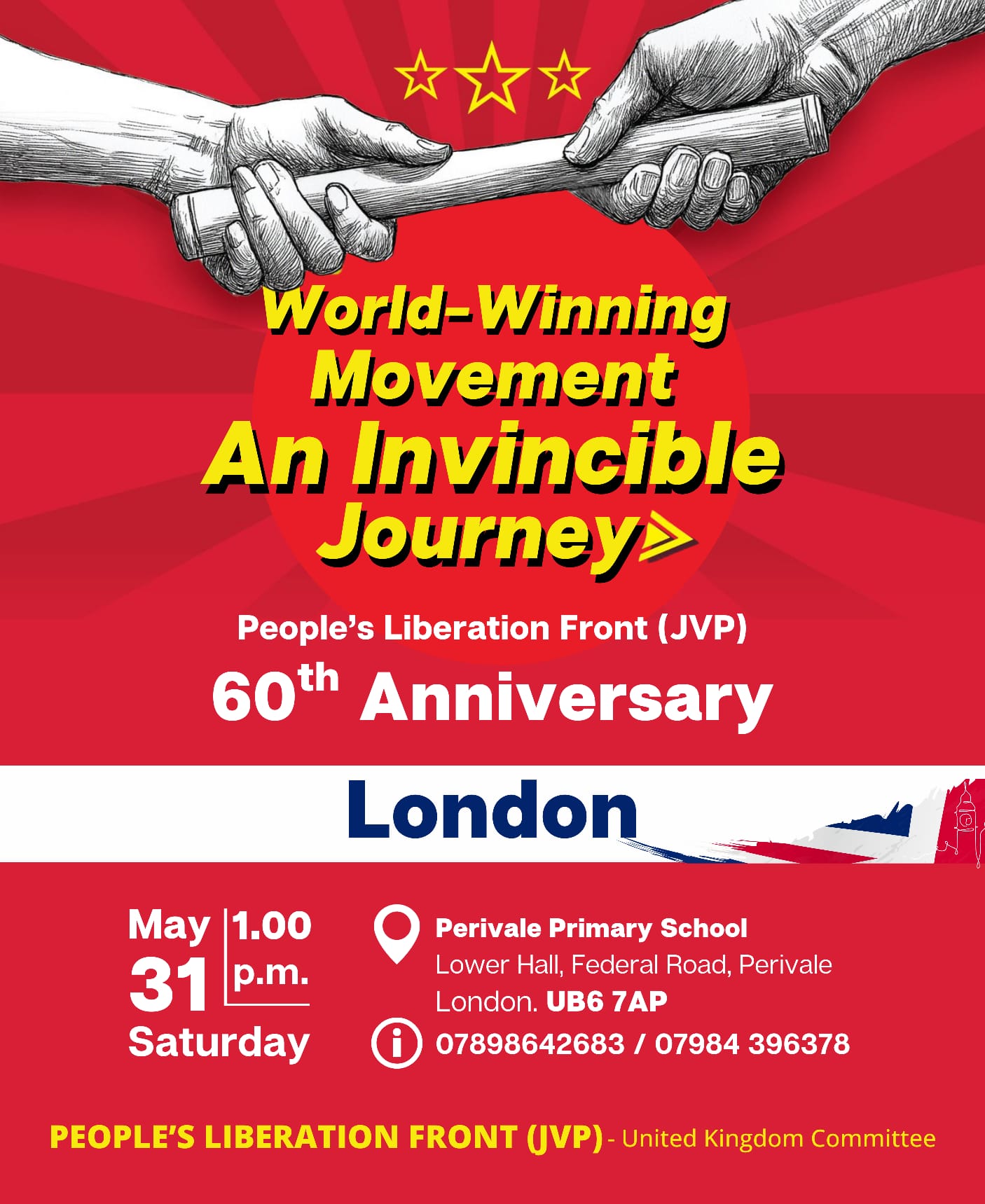

JVP 60th Anniversary Celebration – London

Date - May 31st, 2025 – 1.00 PM

Place - Perivale Primary School, Lower Hall, Federal Road, Perivale, UB6 7AP

* Nearest Tube: Perivale (Central Line)

Tel - Enquiries: 07898 642683 / 07984 396378

Email: [email protected]

-By LeN London Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-05-29 04:20:51)

Leave a Reply