-By LeN Political Correspondent

(Lanka-e-News -05.July.2025, 11.20 PM) Forty-two years on, the shadows of Black July still loom over Sri Lanka's turbulent political history. While mainstream narratives focus on the brutality of the mobs and the rise of Tamil militancy, much of the culpability for the events that unfolded in July 1983 lies at the feet of the ruling regime itself – chiefly President J.R. Jayewardene, then Prime Minister R. Premadasa, and Minister of Youth Affairs, Ranil Wickremesinghe.

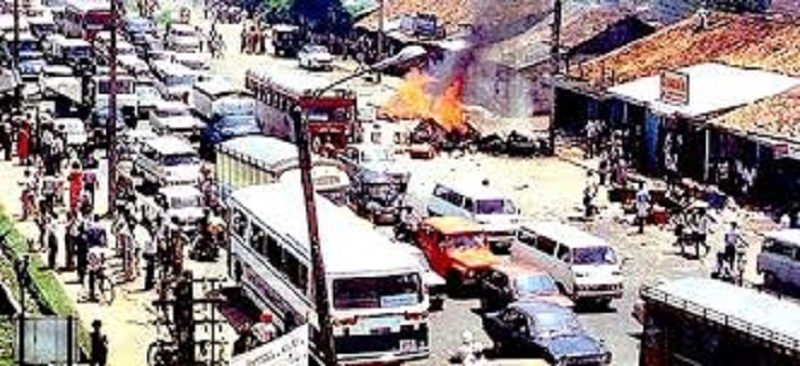

That pogrom – a state-enabled campaign of terror against Tamil civilians – was not a spontaneous outburst of rage. It was calculated, orchestrated, and executed under a watchful state that permitted its streets to burn.

Black July was not just a riot; it was a systematic, week-long pogrom. It followed the ambush and killing of 13 Sinhala soldiers by the LTTE, which was seized upon by the United National Party (UNP) government as a pretext for retribution. What followed was state-tolerated, if not state-sanctioned, violence against Tamil civilians.

More than 3,000 Tamil civilians are believed to have been killed, though official figures claim a mere 300. Thousands of homes and businesses were looted and torched. Trains were stopped; Tamil passengers were pulled out and assaulted. The military and police, far from quelling the violence, often stood idly by – in some cases, they were complicit.

President J.R. Jayewardene’s administration bears the gravest burden. Rather than condemning the atrocities, Jayewardene notoriously justified the violence, suggesting Tamils had to be “taught a lesson.” His failure to declare a curfew or deploy the army in a meaningful manner in the early stages is widely viewed as deliberate inaction.

Soon after the violence erupted, his government passed the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution, effectively disenfranchising Tamil political voices and barring elected representatives who supported Tamil separatism – further alienating the Tamil population.

R. Premadasa, father of current Opposition Leader Sajith Premadasa, was Prime Minister at the time. Though he did not personally orchestrate the attacks, he is believed to have wielded influence over criminal elements in Colombo – particularly in Pettah and Slave Island – who formed the backbone of many of the mobs.

His trusted associate and Mayor of Colombo, Sirisena Cooray, ensured that the Ceylon Transport Board was stocked with loyalists. CTB vehicles were used to transport mobs, weapons, and even fuel – evidence of state resources being used to commit targeted ethnic violence.

Ranil Wickremesinghe, then Minister of Youth Affairs, was not directly implicated in the pogrom, but his proximity to known thugs – including the infamous Gonawala Sunil – raises questions about his silence and indifference. Gonawala Sunil, a convicted rapist later pardoned by President Jayewardene, was seen leading mobs and is reported to have had ties to Wickremesinghe’s political circle.

To this day, no credible inquiry has been conducted into Wickremesinghe’s indirect role during those bloody days.

One eyewitness, then a senior member of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), recalls being stopped in Kelaniya and asked to say “baldiya” – a Sinhala word often used to test if a person was a Tamil or Sinhalese.

“I was spared because I spoke fluent Sinhala,” he recalls. “But the mobs stripped my car of petrol before letting me go. I saw lorries being looted, set ablaze with passengers inside. Armed gangs were roaming with electoral registers, identifying Tamil households.”

He later discovered that Buddhist monks, wearing saffron robes, were part of the marauding mobs – armed with voters’ lists, guiding the destruction with chilling precision.

His Tamil comrades in Kotahena and Maradana were hunted, some murdered. Others survived only through the mercy of neighbours.

Perhaps the most grotesque episode came within the high walls of Welikada Prison. On July 25 and 26, 1983, Sinhalese inmates, armed with improvised weapons, broke into the wards housing Tamil political prisoners.

Thirty-five prisoners were hacked to death on the first day, including Kuttimani and Thangathurai – prominent Tamil leaders. On the second day, 17 more were slain, among them Dr. Somasundaram Rajasundaram, Secretary of the Gandhiyam Movement.

Reports indicate that guards stood by or aided the assailants. Tear gas was used – not to deter the attackers, but on Tamil inmates defending themselves. Prime Minister Premadasa’s reaction was tellingly dismissive: “One Sinhalese prisoner also died.”

The evidence mounts: government lorries transporting fuel and thugs, police standing idle, political figures offering tacit support. Cyril Mathew, a senior UNP figure, had long stoked anti-Tamil rhetoric. His ministry controlled the institutions from which many logistical resources for the riots were drawn.

The burning of the Jaffna Public Library in 1981, an earlier act of cultural violence, was a precursor. It too involved state complicity and marked the beginning of a campaign of cultural erasure and ethnic targeting that culminated in July 1983.

Successive governments have refused to acknowledge the state’s role. No official apology, no war crimes tribunal, no independent commission with teeth.

Instead, false narratives thrive. Even today, prominent figures from the same political lineages attempt to whitewash history. The country is asked to forget – but victims and survivors remember.

It is not merely about Tamil grievance. It is about the failure of the Sri Lankan state to protect its own citizens. The consequences were disastrous: a brutal 30-year civil war, economic devastation, and a divided society.

Black July was the beginning of Sri Lanka’s long descent into blood and ruin. And it was orchestrated not by a mob – but by men in suits, sitting in air-conditioned offices, calculating political advantage.

In a year where elections are again on the horizon, the ghosts of Black July should serve as a dire warning. Politicians must be held to account for past crimes, not rewarded with power.

Justice delayed is not only justice denied—it is a denial of truth, dignity, and peace. The flames that engulfed Colombo in July 1983 did not only burn Tamil homes. They scorched the soul of a nation.

As Sri Lanka stands at yet another crossroads, it must ask itself: will it continue to bury its truth – or will it finally confront the men who lit the match?

-By LeN Political Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-07-05 22:41:40)

Leave a Reply