EU Family Members Penalised in British Nationality Applications Despite Withdrawal Agreement Guarantees

(Lanka-e-News -29.Aug.2025, 11.00 PM) When the United Kingdom concluded its divorce from the European Union, ministers repeatedly reassured nervous communities that the rights of EU citizens and their families would be protected. The EU–UK Withdrawal Agreement, signed and ratified in January 2020, was explicit in its terms: residency rights acquired before the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020 would be safeguarded.

Yet five years on, a growing number of EU nationals and their non-EU family members—many of whom have lived in Britain for decades—are finding that such promises are little more than ink on parchment. Their crime? Failing to apply for the EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS), a bureaucratic requirement that, in their view, should never have superseded the treaty obligations solemnly entered into by the British Government.

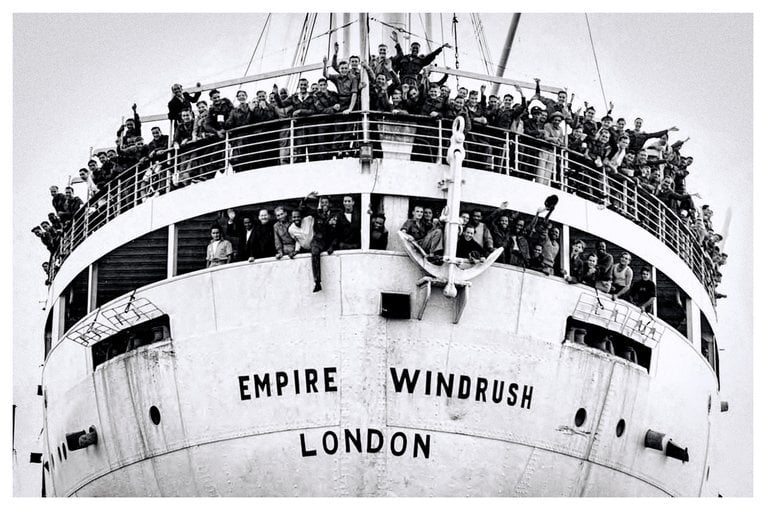

Now, as naturalisation applications pile up, the Home Office is refusing citizenship to long-settled EU family members, citing provisions of the British Nationality Act 1981. Legal experts warn that this apparent disregard for treaty law could ignite a litigation firestorm reminiscent of the Windrush scandal—only this time, it is Europe’s citizens, and their South Asian spouses, caught in the crosshairs of official intransigence.

Part Two, Chapter I (Articles 9–35) of the Withdrawal Agreement sets out the protection of residence rights for EU citizens and their family members residing in the UK before the end of the transition period.

Article 15 is particularly crucial: it enshrines the right of permanent residence. Periods of legal residence accumulated before and after Brexit are to be treated as continuous, allowing those with five years of residence to secure permanence.

In theory, that permanence is unconditional. Yet, in practice, the Home Office now insists that only those who registered under the EU Settlement Scheme—a system created domestically by the UK, not mandated by the Withdrawal Agreement—may be recognised as “free of immigration conditions” for the purposes of British nationality law.

Applicants with EU permanent residence cards, issued before Brexit and validly held, have been met with rejection letters pointing to Section 6(2) of the British Nationality Act 1981, which requires naturalisation applicants to hold indefinite leave to remain (ILR) or settled status at the time of application. The Home Office has interpreted this requirement strictly, refusing to acknowledge permanent residence rights derived from EU law as sufficient.

This, critics say, amounts to a breach of international obligations. “The UK Government signed a treaty guaranteeing that permanent residence rights would continue,” observes Professor Helen KC, an authority on constitutional law. “By substituting a domestic administrative scheme as the sole route to recognition, they are effectively rewriting the treaty by the back door.”

What deepens the sense of injustice is that many of those now penalised were allowed to travel freely in and out of the UK after 2020. Border Force officers, far from warning them of a looming deadline, waved them through.

“No one at Heathrow or Gatwick ever said, ‘You must apply for the Settlement Scheme,’” recalls Ajith Singh an Indian spouse of an Italian national, who has lived in Britain since 2007. “We had our permanent residence cards issued by the Home Office itself. We thought that was enough. They never told us otherwise. Now, suddenly, we are told we are unlawful and cannot naturalise. It feels like a trap.”

For campaigners, this selective enforcement bears an uncanny resemblance to the hostile environment policy that ensnared the Windrush generation. In both cases, the Home Office tacitly permitted individuals to reside, work, and travel, only to later question their legitimacy when paperwork failed to align with shifting bureaucratic expectations.

The legal sticking point is Section 6(2) of the British Nationality Act 1981, which governs naturalisation for spouses of British citizens. Among other criteria, it requires that the applicant be “free from immigration time restrictions” on the date of application.

The Home Office has chosen to interpret this phrase narrowly, equating “free from restrictions” exclusively with ILR or settled status under the EUSS. Permanent residence cards, even when issued by the Home Office itself, are dismissed as inadequate.

Critics argue that this reading ignores the supremacy of international treaty obligations. “Permanent residence acquired under EU law was, by definition, free of conditions,” argues an immigration barrister at Court Chambers. “The Withdrawal Agreement entrenches that right. To refuse recognition is to act in breach of the UK’s own treaty commitments. The courts may well find that domestic law must be read compatibly with the Withdrawal Agreement.”

Indeed, Article 4 of the Withdrawal Agreement explicitly states that the provisions concerning citizens’ rights “shall produce in respect of and in the United Kingdom the same legal effects as they produce within the Union and its Member States.” That includes direct effect and primacy over conflicting domestic provisions.

The comparisons with Windrush are difficult to ignore. Then, as now, the Home Office placed the onus on individuals to prove their lawful residence, despite having itself issued documentation confirming their status. Then, as now, individuals were blindsided by policy shifts and retrospective reinterpretations.

The Windrush scandal ultimately forced the Government into an apology, compensation schemes, and ministerial resignations. The cost, both financial and reputational, was enormous.

“This is Windrush 2.0,” declares Sarah , director of the Jesuit Service UK. “Only this time, it is not Caribbean migrants, but European citizens and their non-EU spouses, many of whom are from South Asia. The pattern is the same: people who built lives in Britain, trusted government documents, and are now told they were mistaken all along.”

The issue is no longer confined to British shores. In one extraordinary development, a US citizen married to an EU national has lodged a formal complaint with the US State Department, alleging discrimination in the UK’s handling of nationality applications.

Diplomatic sources in Washington confirm that the complaint is under review. While it is unlikely to trigger sanctions, it signals the growing unease among allies at Britain’s post-Brexit immigration enforcement.

Brussels, too, is monitoring the situation closely. The European Commission has previously warned that failure to implement the Withdrawal Agreement faithfully could lead to legal action under the dispute resolution mechanisms contained in the treaty.

Law firms across London and beyond report a surge in inquiries. Judicial review proceedings are already being prepared, with claimants arguing that the Home Office is unlawfully refusing naturalisation applications that should, under treaty law, be accepted.

If successful, the litigation could expose the Government to thousands of claims. The financial consequences could be staggering. “The compensation bill could dwarf Windrush,” warns by leading Immigration Expert. “We are talking potentially billions, once legal costs, damages, and administrative redress are factored in.”

Perhaps most troubling is the disparate impact on non-EU family members, many of whom are South Asian spouses married to European nationals. While EU citizens themselves were more likely to hear of the Settlement Scheme through their consulates or community networks, their Sri Lankan, Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi partners often remained in the dark.

Campaigners suggest this disproportionate harm may expose the Home Office to claims of indirect racial discrimination, further compounding its legal vulnerability.

The Government faces a stark choice. It can either:

Acknowledge permanent residence rights under the Withdrawal Agreement, allowing those with valid cards to naturalise without retrospective penalty; or

Dig in its heels, continue rejecting applications, and face an avalanche of court cases, adverse judgments, and international condemnation.

Some MPs are already calling for reform. the Green Party MP , has tabled questions in Parliament, warning that “another Windrush scandal is in the making.”

For the individuals caught in the middle, the stakes are intensely personal. “I have lived in Britain for 20 years,” says Ajith Singh. “My children are British. My wife has Italian and British nationalities. How can they tell me I do not belong here? It is cruel, and it is wrong.”

The Windrush scandal was meant to be a turning point, a warning to future governments about the dangers of bureaucratic rigidity and the human cost of a hostile environment. Yet, barely a decade later, the Home Office seems poised to repeat the same mistakes—this time against European families who were promised certainty.

Unless ministers intervene to reconcile domestic nationality law with the Withdrawal Agreement, Britain risks not only breaching international law but also squandering what little goodwill remains in its post-Brexit diplomacy.

And for thousands of families—Sri Lankan, Italian, Polish, Bangladeshi, and beyond—the price will be measured not in headlines or court judgments, but in lives upended, futures denied, and trust once again shattered.

-By A Special Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-08-29 18:39:56)

Leave a Reply