-By LeN Political Correspondent

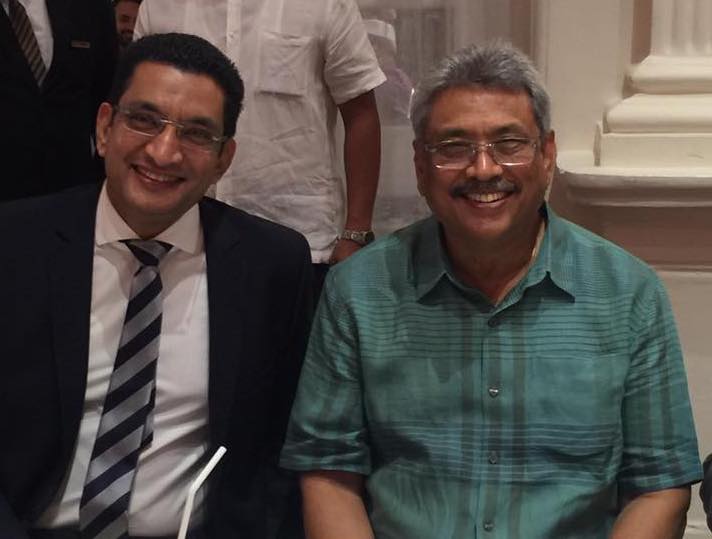

(Lanka-e-News - 10.Oct.2025, 11.00 PM) When Ali Sabry, legal representative to Gotabaya Rajapaksa, strode into a packed press room in November 2019 clutching a blue-bound American passport, the message was clear and theatrical.

Standing beside campaign officials, he declared that Rajapaksa — the war-hero-turned-presidential-hopeful — was no longer a U.S. citizen, that the formal renunciation had been completed, and that all relevant documentation had been duly submitted to the Sri Lankan Election Commission.

Sabry’s calm authority that day silenced critics, quelled legal anxieties, and paved the way for Rajapaksa’s sweeping victory at the ballot box.

But six years later, under the reform-driven National People’s Power (NPP) government, the foundations of that moment are cracking. A leaked internal memo from the Election Commission, obtained by international investigative media and verified by Lanka E News, now raises disturbing questions:

Was the renunciation ever complete at the time of Rajapaksa’s nomination?

And, more gravely, did Ali Sabry — now a destitude and isolated figure and former foreign minister and Justice Minister — mislead the Election Commission and the public?

It was late October 2019, just weeks before Sri Lanka’s presidential election. Opposition parties were in uproar, claiming that Rajapaksa, who had lived in California for years and held dual nationality, was ineligible to contest.

Under Sri Lankan law, dual citizens cannot hold public office. To run for president, Rajapaksa had to prove that he had formally renounced his American citizenship — a process that, under U.S. law, is neither instantaneous nor politically trivial.

The U.S. Department of State’s standard procedure involves an in-person interview, submission of Form DS-4079 (Statement of Voluntary Relinquishment of U.S. Nationality), payment of a fee, and — crucially — the issuance of a Certificate of Loss of Nationality (CLN), the only legal proof that renunciation has taken effect.

Yet, on 3 November 2019, at a press conference that dominated every local television channel, Sabry told the nation that Rajapaksa’s renunciation was “complete,” holding up a passport and several papers as “proof.”

“This matter is over,” Sabry said at the time. “Gotabaya Rajapaksa is no longer a citizen of the United States.”

Last month, an internal document from the Sri Lankan Election Commission leaked to a regional investigative consortium, later shared with Lanka E News Insight Team, reignited the debate.

The memo, dated November 2019, records that the Commission had received no formal documentation from the U.S. State Department, only a copy of a renunciation application allegedly filed with the U.S. Embassy in Colombo.

The note, signed by a senior official and addressed to the then-Chairman Mahinda Deshapriya, states:

“No Certificate of Loss of Nationality or confirmation from the U.S. State Department has been produced. Only an unsigned application for renunciation was viewed during the consultation with counsel representing Mr. Rajapaksa.”

If accurate, the document undermines the very basis on which Rajapaksa’s candidacy was validated.

Former U.S. consular officials contacted by Lanka E News confirmed that no renunciation of citizenship can be completed within days, as implied by Sabry’s statement.

“Even in expedited cases, it typically takes between six and eight weeks from the date of the renunciation interview before a CLN is issued,” says Daniel , a retired U.S. State Department legal adviser. “Until that certificate is approved and signed by Washington, the individual remains a U.S. citizen in the eyes of U.S. law.”

The U.S. Embassy in Colombo, responding to earlier media inquiries, maintained that it could not comment on “individual citizenship matters.” But an embassy source, speaking on background, confirmed that no CLN had been issued to Gotabaya Rajapaksa prior to November 2019.

The Election Commission, chaired then by Mahinda Deshapriya, certified Rajapaksa’s eligibility despite the absence of official verification from Washington.

A senior Commission official, now retired, told Lanka E News:

“We were under intense political pressure. The documentation presented was not conclusive, but we were assured by legal counsel — Mr. Sabry himself — that the renunciation had been accepted by the U.S. authorities.”

The official, who requested anonymity, added:

“There was a sense that questioning the submission too deeply would provoke political turmoil. We trusted the representations made to us.”

Those representations, if proven false, could amount to criminal misrepresentation under Sri Lankan election law and falsification of official documents under both Sri Lankan and U.S. statutes.

The NPP government, elected on a platform of transparency and anti-corruption, has quietly reopened the case. A senior official at the Ministry of Justice confirmed to Lanka E News that “a preliminary review” has begun into the conduct of Ali Sabry and the certification process surrounding Rajapaksa’s candidacy.

“This is not about political revenge,” the official said. “This is about ensuring that the rule of law applies equally to everyone — including lawyers who represented a presidential candidate.”

The review will reportedly examine:

What documents were actually submitted to the Election Commission;

Whether those documents included or omitted the CLN;

Whether any official at the Commission was threatened, misled, or coerced; and

Whether Ali Sabry’s public statements constituted intentional misrepresentation.

If investigators determine that Sabry knowingly presented incomplete or misleading documentation, the legal consequences could be severe.

Under Sri Lankan law, providing false information to a constitutional body such as the Election Commission constitutes a criminal offence. Under the recently enacted Proceeds of Crime and Misrepresentation Act, the penalties could extend to disqualification from public office and loss of civil rights.

In the United States, pretending to have renounced citizenship — or presenting oneself as having done so before the process is legally finalized — can constitute a violation of federal law, especially if done for political or financial gain.

International legal analysts suggest that Colombo and Washington could, in theory, initiate a joint investigation under mutual legal assistance treaties (MLATs) to verify the authenticity of the documents presented in 2019.

Ali Sabry, once seen as one of Sri Lanka’s most articulate lawyers and later the country’s Foreign Minister, has so far remained silent on the renewed allegations.

Attempts by Lanka E News to reach Gotabaya Rajapaksha through his office went unanswered. However, in previous interviews, he has maintained that “all procedures were duly followed” and that the “renunciation matter was verified with the relevant authorities.”

Critics within Colombo’s legal fraternity are less forgiving.

“Sabry is a Show man lawyer,” says Dr. Silva, a constitutional law expert at Colombo. “But brilliance does not absolve one from accountability. If he knowingly misrepresented facts before the Election Commission, it is not only unethical — it is criminal.”

Rajapaksa himself faces potential exposure. If it is proven that he remained a U.S. citizen at the time of his nomination and election, his presidency could, retrospectively, be declared constitutionally invalid.

Legal experts point out that such a finding would set a historic precedent — one that could lead to the nullification of decisions made during his presidency, including key appointments and defence contracts.

“The implications are enormous,” says former Supreme Court Justice with anonymity “This would raise questions about the legality of the entire Rajapaksa administration. The chain of command, the cabinet, even international agreements signed under his presidency — all could face legal challenge.”

According to documents reviewed by Lanka E News, Rajapaksa initiated his renunciation process at the U.S. Embassy in Colombo in early August 2019. But the U.S. State Department’s own publicly released records show that the corresponding CLN for “Gotabaya Nandasena Rajapaksa” was issued only in December 2019 — weeks after his election victory.

This discrepancy directly contradicts Sabry’s assertion that the renunciation was “complete” by early November.

An international legal expert familiar with the case remarked:

“If the CLN was issued after the election, it means Rajapaksa was still an American citizen when he contested. The rest is politics — but the law is black and white.”

The controversy has also revived a broader debate about the culture of impunity that has long haunted Sri Lankan politics — where legality often bends before political expediency.

For years, allegations of falsified documents, manipulated records, and selective enforcement of law have eroded public trust. The Rajapaksa citizenship saga, critics argue, epitomises that malaise.

“The issue is not whether Gotabaya won the election fairly,” says Dr. Pathirana, a political scientist. “It’s whether the system allowed him to run fairly in the first place.”

The NPP government’s legal task force is expected to summon officials from the Election Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and possibly the U.S. Embassy to provide testimony.

If evidence confirms deliberate deception, prosecutors may seek to indict both Sabry and any complicit officials under the Public Property and Misrepresentation Act.

Washington’s cooperation will be key. The U.S. could provide certified copies of the renunciation timeline — effectively settling the question of when Rajapaksa’s citizenship officially ended.

For many Sri Lankans, the issue transcends one lawyer’s conduct or one president’s paperwork. It speaks to a larger yearning for truth after decades of opaque governance.

“Citizenship is not a technicality — it’s the core of constitutional legitimacy,” says attorney Fernando, a member of the Bar Association’s reform committee. “If the system was manipulated once, what prevents it from happening again?”

Perhaps the most profound fallout will be within Sri Lanka’s legal community itself.

Sabry, once hailed as a model of professional ethics, now faces scrutiny from the very institutions that once celebrated him.

Bar Association insiders confirm that a disciplinary inquiry could follow the state investigation. “We cannot allow any member, however senior, to undermine the sanctity of legal representation before a constitutional body,” said one senior member.

As investigators pore over faded documents and archived press footage of that November 2019 press conference, one image remains indelible — Ali Sabry holding aloft a passport, proclaiming the end of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s American citizenship.

If the evidence now emerging is accurate, that moment may come to symbolise something else entirely: the day Sri Lankan democracy was misled by theatre disguised as truth.

The outcome of the investigation could redefine not only the reputations of a former president and his counsel but also the credibility of Sri Lanka’s institutions themselves.

For a nation still healing from corruption and political deceit, the truth — even half a decade late — might finally be the most powerful act of justice.

-By LeN Political Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-10-10 19:54:38)

Leave a Reply