-By LeN External Affairs Correspondent in New Delhi

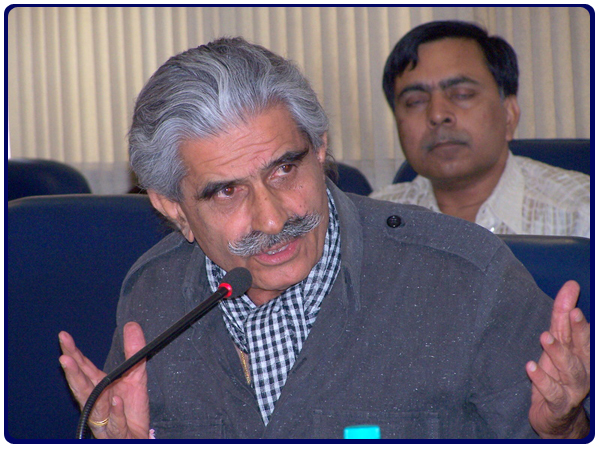

(Lanka-e-News -08.Nov.2025, 11.00 PM) On 4 November 2025, at the venerable halls of the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA) in Sapru House, New Delhi, a seasoned soldier delivered more than a speech — he delivered a challenge. As Sajith Premadasa, Leader of the Opposition of Sri Lanka, took the dais to address “India-Sri Lanka Bilateral Relations,” the audience expected polished diplomacy, soft assurances and political gestures. What they got was a blunt, piercing question from retired Ashok K. Mehta: “How do you intend to implement the 13th Amendment?”

It was a moment of reckoning. Mehta, a former major-general of the Indian Army with tens of thousands of hours of command and campaign experience, was not inviting a rhetorical flourish or a glossed statement. He wanted detail, substance. Premadasa’s reply—“As Opposition Leader, it is not for me to answer, it is for the government”—was at once revealing and damning.

In that split-second exchange, two metaphors collided: one of a warrior-intellectual demanding concrete plans, the other of a politician content with eloquent verbiage. The result? A national embarrassment for Sri Lanka’s opposition and a reminder that substance still matters in a region beset by noise.

Let’s begin with the credential armoury. Ashok K. Mehta commissioned in 1957 into the 5th Gorkha Rifles of the Indian Army. He served in the wars of 1965 and 1971, led internal security operations, studied at the Royal College of Defence Studies (UK) in 1974, and at the U.S. Command & General Staff College in 1975.

His last uniformed appointment: General Officer Commanding the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) in Sri Lanka, 1988-90. After retirement in 1991, he became a veteran analyst, author of multiple books on Indian Army operations .When Mehta raised a question in Sapru House, it came with the weight of decades of experience: operations, doctrine, geopolitics. He didn’t mince words. He didn’t offer sugar-coating.

The setting deserves a quick sketch. The ICWA, India’s premier foreign-affairs think-tank, assembled diplomats, academics and South-Asia watchers. The Sri Lankan Opposition Leader arrived in New Delhi on a visit emphasising Sri Lanka’s economic recovery and investment ties with India.

Premadasa’s presentation touched on “triple tragedies” – the Easter Sunday terror attacks, the COVID-19 pandemic and Sri Lanka’s economic collapse. “India’s support is indispensable,” he declared to polite applause.

But the tone changed when the Q&A began and Mehta took the floor.

Mehta asked: “Mr Premadasa, you spoke of bilateral cooperation and investment, and you pledged to implement the 13th Amendment. But as a politician from Sri Lanka, you know that the 13th Amendment is not a mere clause—it is a structural shift in the Sri Lankan Constitution, designed for genuine decentralisation, including police powers, finance, merger of Northern & Eastern provinces, and a power-sharing model. Yet in Parliament your party has not engaged robustly with this issue.”

Premadasa’s response was disappointing in its shallowness. He replied that the matter lay with the government and as opposition leader he could only “facilitate” it. The audience shifted uncomfortably. The general’s gaze suggested: Soldier, unit, mission, plan. Politician, catch-phrase, non-answer, move on.

In the diplomatic and think-tank world, this was not mere theatrical embarrassment — it was an exposure of substance deficiency. The protocol said “question”, the content was “You haven’t a plan.” In other words: the man who chose to avoid the lesson was being taught it by a soldier-turned-scholar.

For Sri Lanka, the implications go beyond one event. They touch on the credibility of political leadership, the maturity of public debate, and the international image of its governance.

Educational & credibility questions

Premadasa’s bio declares a degree from the London School of Economics and the University of London. But doubts have circulated: Did he sit exams? Did he earn the degree in the conventional way? Who audited the credentials? In governance and diplomacy, this kind of uncertainty becomes a distraction and a vulnerability.

Opposition performance in Parliament

Critics in Colombo argue that the opposition has been noisy but ineffective. Many of its questions on corruption, central-fund misuse and executive accountability have been superficial. If an opposition leader cannot answer detailed foreign-policy/constitutional questions when pressed, what hope is there for integrity in legislative scrutiny?

International perception

In New Delhi, diplomats and analysts took note. The South-Asia analyst in the front row scribbled: “Poor transparency, low planning, high rhetoric.” When the Sri Lankan opposition leader addresses India — a crucial neighbour — they expect substance not stolidity. The exchange at ICWA raised questions: Can this man negotiate Sri Lanka’s future with India if he cannot answer within his own house?

Constitutional reform question

The 13th Amendment remains unresolved — an elephant in Sri Lanka’s governance room. Its ambiguity fuels Tamil grievances, Indian concerns and regional instability. If the Sri Lankan opposition fails to engage meaningfully on it, then talk of decentralisation remains hollow. This matters strategically for Colombo and New Delhi alike.

One of the more subtle themes of the evening: linguistic performance versus substantive clarity. Premadasa used polished English, peppered with older-style vocabulary (“we shall endeavour,” “synergise,” “facilitative modalities”), and seemed to distance himself from the common vernacular. That style may impress domestically, but in an intellectual forum like ICWA, the audience expects crisp analysis. After 20 minutes of “high English”, the question from the floor exposed the gap: an opposition leader not speaking like an academic but doing so in a way that seemed disconnected from his own party’s performance and his own national constituency.

In short: high vocabulary does not substitute for high content. Mehta’s pointed ask — “show us the plan, tell us the how, not the what” — exposed the mismatch.

In Sri Lankan political culture, pedigree often matters. Premadasa’s father, Ranasinghe Premadasa, was President of Sri Lanka (1989-93), an achievement that buys lasting brand value. But brand without substance can backfire. Critics cite background points: the mother of Premadasa worked as a cinema canteen attendant; his father did not even sit the ordinary-level exam (according to some sources); there have been allegations of the family’s associations with fake-notes and unresolved educational-expense questions. Whether all claims are true or not, the irreducibility of such suspicions weighs heavily in public scrutiny — and even more so when leadership is challenged to answer tough questions abroad.

A politician’s background matters — the public looks for authenticity. At Sapru House, the international audience saw through the veneer.

Why did Mehta pick the 13th Amendment? Because it remains a centrepiece of Sri Lanka’s constitutional-security issue:

Introduced in 1987 under the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord as a power-sharing vehicle between centre and provinces;

Intended to decentralise police, financial and administrative powers;

Particularly aimed at the Northern and Eastern provinces (Tamil-majority zones) where a merger clause exists;

Has never been fully operational or relevant; political will has been sporadic; it has mutated into a white elephant.

In effect, the 13th Amendment is a test of whether Sri Lanka can truly handle internal conflict, regional autonomy and Indian-Sri Lanka strategic trust. Mehta’s question to the opposition leader was: “If you don’t have a plan for this Amendment, you don’t have a plan for Sri Lanka’s future.”

If the leading opposition rarely speaks of it, seldom presses for its enforcement, and cannot answer in an international forum, how will the country move forward? And if the opposition cannot, the governing party is worse off.

Within Sri Lanka, the opposition’s recent performance gives material for concern. Instead of becoming the credible alternative, it has often been seen as a noisy adjunct of the system. Key corruption allegations — such as the misuse of the Central Cultural Fund — have been raised in Parliament but not driven to independent commission-inquiry level. Strategic oversight of the government’s security and foreign-policy footprint (particularly vis-à-vis India and China) has been muted. Given these deficits, the leader of the opposition being caught unprepared on the global stage multiplies the damage.

One former diplomat told me, on condition of anonymity: “If you can’t answer soldiers in Delhi you cannot command governments in Colombo.” That may sound harsh, but in geopolitics credibility matters.

We cannot ignore the broader context. Sri Lanka sits at the crossing of strategic cables: Indian-Ocean chokepoints, Chinese infrastructure investment (Belt & Road etc.), Indian Neighbourhood-First policy, and the Indo-Pacific game. India expects a Sri Lanka which is stable, transparent, accountable and able to engage with substance. When a Sri Lankan political figure arrives in Delhi and offers rhetoric but not detail, it affects how India, diplomats, and investors view the country. The opposition leader’s trip was meant to reassure India of future cooperation — instead, he appeared unprepared for the hard question.

Does this matter? Yes — if Sri Lanka wants to balance China and India, to attract finance, to build credible institutions, then its key leadership must be able to engage at the intellectual-practical junction. The slip at ICWA suggests otherwise.

Let’s map the cost:

Domestic trust erosion. If the opposition cannot answer basic questions, voters begin to ask: what do you stand for? Are you an alternative or part of the theatrical show?

International credibility. Investors, foreign governments, think-tanks will mark you down. The world remembers how you answer, not just what you say.

Strategic vulnerability. In South Asia, small states cannot rely on sentiment alone; they must present credentials, plans, governance capability. When the opposition leader publicly flounders, it sends signals to partners and adversaries alike.

Institutional stagnation. The 13th Amendment remains unresolved. When neither government nor opposition treats it seriously, reform becomes mythical, grievances persist, strategic peace remains elusive.

Imagine an alternate script. Premadasa arrives in Delhi, addresses India-Sri Lanka relations, then when asked about the 13th Amendment he pulls out a one-page roadmap:

Step 1: Establish a joint working group Liberating Implementation of 13A, chaired by opposition and government ministers.

Step 2: Within 60 days, present to Parliament the progress report on police powers in the North.

Step 3: Engage civil society and Tamil diaspora in North-East to draft merged-province option oversight.

Step 4: Seek Indian technical assistance (as per 1987 accord) for institutional capacity.

He might say: “I commit today that my party will table a private-member bill in the next sitting. I will bring to India a joint Sri Lanka-India working paper.” That would have shown not only awareness but leadership. Instead, the question died.

Several factors appear to converge:

Over-reliance on pedigree and brand. Premadasa inherits a political name but seems to have rested too much on that rather than building a strategy for reform-based leadership.

Emphasis on fluency over clarity. A polished English presentation may look good domestically, but in global forums it simply raises expectations—and the gap becomes embarrassing.

Lack of focus on core governance issues. The opposition is often reactive, not proactive. Without a clear constitution-governance-security agenda, rhetoric fills the vacuum.

Structural weakness of party and parliament. When your own party does not widely engage in detailed reform debates (for example on the 13th Amendment), you cannot pretend to be expert on it when abroad.

This incident is not just about one man, one question, one Think-Tank. It reflects a broader malaise: the substitution of sound-and-fury for strategy and substance. Sri Lankan politics has too often rewarded noise, theatrics and personality over institutions, policy and preparedness.

In the age of geopolitics, of strategic partnerships, of high-stakes economics, small states like Sri Lanka cannot afford to send unprepared or superficial leadership to the global stage. India will not sign its cheques when the Sri Lankan interlocutor cannot articulate a credible governance roadmap. China will not invest deeply when the politics next door is seen as transactional, not structural.

For the opposition leader this means: your job is not just to oppose—but to offer alternative. To be heard in Colombo is one thing; to be credible in Delhi, Geneva and Colombo is another.

Will this episode register in Sri Lanka? Will the opposition leadership regroup? Will civil-society analysts record it as a turning point? Possibly.

In the parliament that followed, commentators noted that journalists asked sharper questions: about the opposition’s internal educational-expense disclosures, about how many exams the leader actually sat, about the degree certification process. The optics of being caught flat-footed on a strategic question carry weight.

In New Delhi, diplomatic back-channels are likely to note the incident quietly, and ask: if the opposition comes to India offering cooperation, does it bring policy substance or just photo-ops? The message for Sri Lanka is clear: substance > soundbites.

Major-General Mehta’s wake-up question was metaphorical but serious. He did not slap the opposition leader physically — but the intellectual body-blow delivered at ICWA was heard loud and clear. For Sri Lanka’s politics, the challenge is no less real.

If the opposition refuses to engage at the level of “how”, it leaves the field open not just for the government but for external actors. If constitutional reform, decentralisation and governance restructuring remain on the back-burner, Sri Lanka’s strategic autonomy, internal peace and international standing remain fragile.

The anthem of populist politics will not suffice. The treaties, amendments and bilateral engagements demand clarity, planning and follow-through. The next time a Sri Lankan statesman stands before India’s elites, the default question will no longer be “what will you say?” but “what will you do?”

If the opposition leader cannot answer that, then the real slap has already been administered — by history.

-By LeN External Affairs Correspondent in New Delhi

---------------------------

by (2025-11-09 00:10:37)

Leave a Reply