-By LeN Political Correspondent

(Lanka-e-News -28.Nov.2025, 11.00 PM) Sri Lanka, once again, is under water.

Floods ravaging all 25 districts have displaced hundreds of thousands, collapsed bridges, submerged townships and battered a country already weighed down by economic strain. But unlike the nation’s darkest December—26 December 2004—this time the country watches a very different kind of government response unfold. And as the torrents rise, so too does an older, unresolved question: what happened to the Rs. 82 million siphoned to the infamous “Helping Hambantota” account?

Two decades on, the scandal has returned to public conversation with the same force as the floodwaters breaching dams and dragging houses into rivers. The reason is simple: the contrast between the NPP government’s transparent, centralised disaster-management efforts in 2025 and the shady, improvised financial channels during the 2004 tsunami could not be more glaring.

This is the story of the flooding—and the scandal it resurrected.

On the morning of 26 December 2004, Sri Lanka suffered one of the most devastating natural disasters in its recorded history. The Indian Ocean tsunami swallowed homes, ploughed through hotels, tore up railway tracks and left over 30,000 people dead. More than half a million were displaced.

President Chandrika Kumaratunga was in London, leaving the state’s emergency management in the hands of Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, then only a year away from the presidency.

As foreign nations, Sri Lankan expatriates, NGOs and ordinary people from across the world scrambled to send help, money began pouring in without precedent. It was the first time in modern Sri Lankan history that the island received such swift, unfiltered global goodwill.

Yet, in that historic moment of humanitarian unity, a parallel tragedy was unfolding.

In the frantic days following the tsunami, money handed over to the Prime Minister or the PM’s Office went into a temporary government account titled “Secretary to the Prime Minister.” With no formal fund established yet, all incoming donations were supposed to be transferred into an official state mechanism.

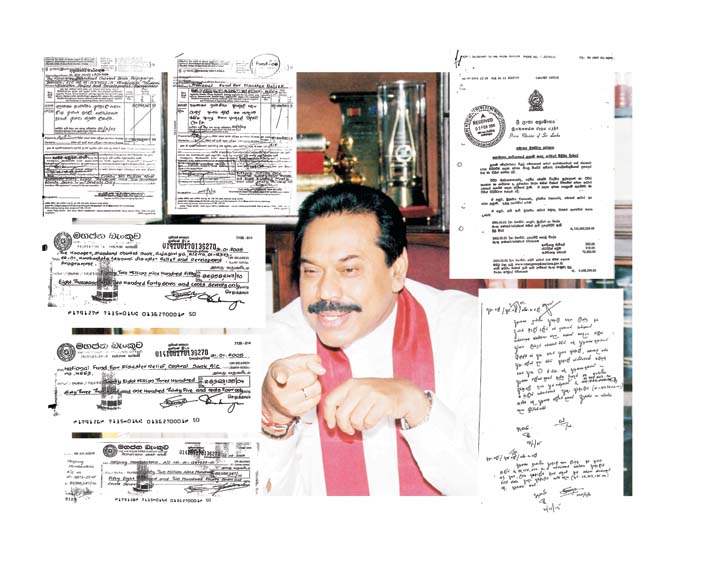

But my investigation, conducted through insider testimonies, bank records and confidential PM’s Office documents, uncovered a far more troubling story.

A colossal Rs. 82,958,247.70 was transferred from the Prime Minister’s Punarjeewana (Reconstruction) Fund into a private bank account held at Standard Chartered Bank, Rajagiriya. This account was not government-controlled. It was called:

Helping Hambantota

Account No. 01-1237322-01

The money belonged to the Sri Lankan people.

The account belonged to a group of private individuals.

Among the four signatories were:

Prof. Epasinghe – Rajapaksa’s long-time friend, a private citizen

Mahinda Gunawardena – Rajapaksa loyalist

Chamal Rajapaksa – the PM’s brother

Udaya Abeyratne – Accountant at the Road Development Authority

Not one of them was authorised under government financial regulations to preside over public donations.

At the time the account was examined—29 June 2005—it held over Rs. 103 million.

It was still receiving cash deposits.

When President Kumaratunga returned from London, she issued a clear directive through Presidential Secretariat Circular PA/272 (29 December 2004):

*“All tsunami relief donations must be deposited into one central account at People’s Bank: ‘President’s Fund for Disaster Relief.’

No ministry or public institution is authorised to maintain separate accounts.”*

The Prime Minister’s Secretary, Lalith Weeratunga, received this directive.

Yet, in a clear act of defiance:

He opened a new official PM’s fund at People’s Bank (Punarjeewana Fund).

He simultaneously facilitated the transfer of Rs. 82 million from that fund into the private Helping Hambantota account.

He provided no written donor instructions indicating these funds were meant “for Hambantota only.”

He authorised the movement of public funds into private hands contrary to Presidential policy.

This was not merely an administrative lapse.

It was a structural redirection of the nation’s most emotionally charged donations.

The more one examines the movement of funds, the more glaring the irregularities become.

No Written Donor Instructions

Not one donor—out of the 22 arbitrarily marked as “Hambantota Only”—had provided written consent or documentation stating their contribution must be used exclusively for Hambantota district.

Fake Legitimacy Via Media Exposé

In February 2005, the PM’s Office placed a full-page advertisement listing donors.

The list was cleverly split:

22 donors for Hambantota → totalling just over Rs. 82 million

33 donors for Sri Lanka → totalling Rs. 28 million

The exact amount that had mysteriously travelled into the private Helping Hambantota account.

The Private Account Had No Legal Basis

Helping Hambantota:

was not a registered NGO

was not a trust

was not a government entity

had no board appointed through legal framework

was opened solely on verbal instructions from the PM’s Office

Standard Chartered Bank, for reasons unknown, failed to demand the standard documentation required for accounts holding public donations.

For a brief period, over Rs. 100 million of public money sat unguarded in a private account with no financial regulations, no audit oversight and no tender procedure.

The tsunami’s victims remained in tents.

Their money rested in a Standard Chartered call deposit earning interest.

Under Sri Lankan law, particularly the Offences Against Public Property Act and Penal Code provisions on criminal breach of trust, the following concerns arise:

Misappropriation of public property

Violation of Presidential directive

Diversion of donations meant for nationwide disaster relief

Use of private individuals as signatories for public funds

Absence of procurement transparency

Legal experts I consulted described the case as:

“One of the most clear-cut examples of a public official privately ring-fencing disaster funds under the guise of constituency development.”

But no prosecution came.

Political winds shifted.

Rajapaksa soon become President.

And the tsunami gave way to war, then debt, then forgotten history.

Until now.

Fast-forward to 2025.

Sri Lanka is again submerged—this time from monsoon flooding devastating all 25 districts.

The death toll rises.

Rivers burst their banks.

Entire towns in the South, North, East, and Central Provinces vanish underwater.

But the response could not be more different from 2004.

A Centralised, Transparent Emergency Command

The NPP Government, within hours, mobilised the Army, Navy and Air Force across all districts.

A Rs. 30 billion emergency fund was immediately allocated with full public disclosure.

Disaster Management Authority updates are broadcast hourly.

A universal 24/7 emergency hotline for every district was activated.

State resources were redeployed without political exclusion.

Most remarkably, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake took a step almost unheard of in Sri Lankan political history:

He invited the Leader of the Opposition, Sajith Premadasa, to join the national disaster command team.

No rival camps.

No political monopolies.

No private accounts quietly opened under party loyalists.

Instead:

Unity. Transparency. Accountability.

For the first time in decades, Sri Lanka’s disaster response looks like a state effort—rather than a party operation.

7. Why “Helping Hambantota” Matters Again

The floods have brought with them more than mudslides and swollen rivers—they have resurfaced an unresolved national trauma.

For many Sri Lankans, the 2004 scandal was not merely about missing money.

It was about betrayal.

Money donated by grieving foreigners, by factory workers in Milan and taxi drivers in Sydney, by schoolchildren in Oslo, by UN staff in New York—ended up in a private bank account run by political loyalists.

Today, as the NPP government distributes aid transparently, the comparison is inevitable.

The question haunting the public is not just:

“How much was stolen?”

but

“What would Sri Lanka’s disaster resilience look like today if 2004 had been handled honestly?”

How many homes could have been built?

How many schools could have reopened?

How many communities could have been rebuilt faster?

How much trust in government might have been preserved?

As the new floods recede, Sri Lankans confront a choice:

Let the past drown again in the rising waters,

or

Reopen the file marked HELPING HAMBANTOTA and demand accountability that was never delivered.

This moment—this flood—has placed an old scandal under a new spotlight.

It is not revenge the public seeks.

It is closure.

And assurance that no future leader—no matter how powerful—will ever again transfer national tragedy into private opportunity.

Because in today’s Sri Lanka, floodwaters rise quickly.

But public memory, it seems, rises faster.

-By LeN Political Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-11-28 18:26:39)

Leave a Reply