The border affray is a sign of worrying military escalation between Asia’s giants

(Lanka-e-News -17.June.2020, 3.00PM) The two armies each had guns, artillery and tanks to the rear. But they wielded only sticks and stones at the front, as night fell on June 15th. That was deadly enough. When the brawl ended, and the final rocks had been thrown, at least 20 Indian troops lay dead in the picturesque Galwan valley, high in the mountains of Ladakh. Chinese casualties are unknown. They were the first combat fatalities on the mountainous border between India and China in 45 years, drawing to a close an era in which Asia’s two largest powers had managed their differences without bloodshed.

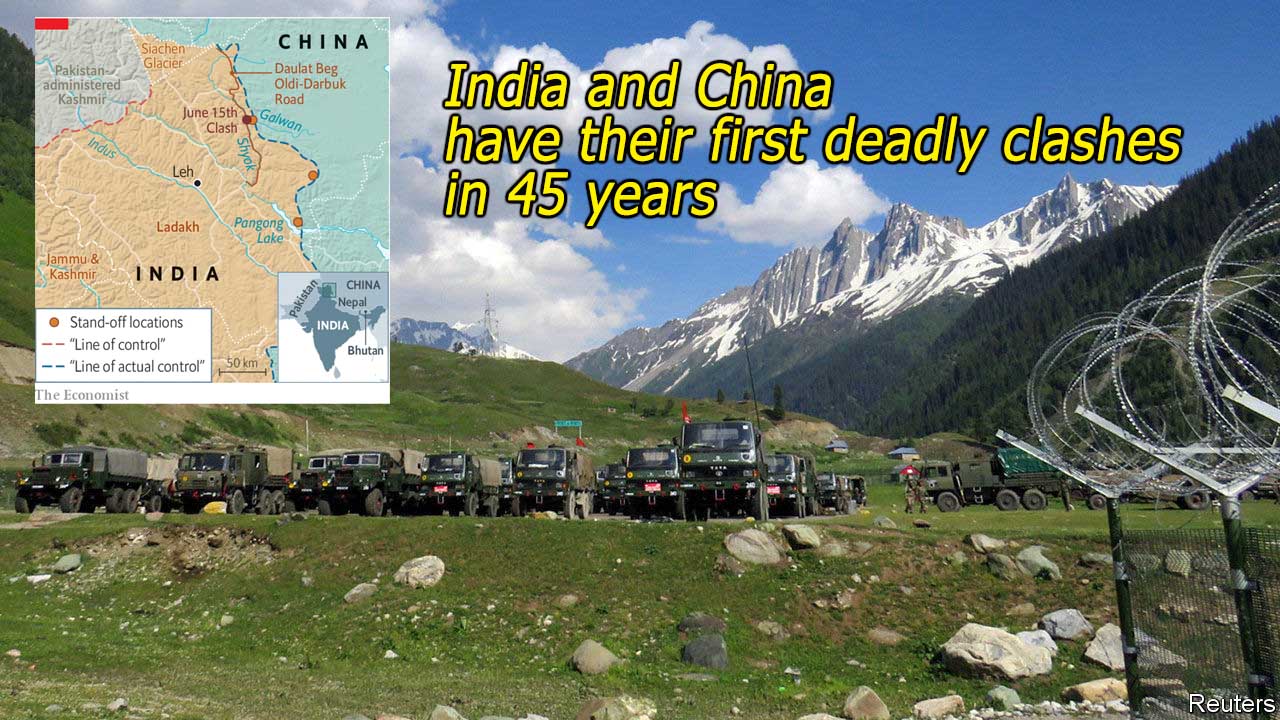

The Indian and Chinese armies had been locked in a stand-off at three sites in Ladakh, an Indian territory at the northernmost tip of the country, for over a month. In April the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) broke off from exercises and occupied a series of remote border posts along the disputed frontier, known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Both sides quickly moved troops and heavy weapons towards the LAC. As troops squared off, punch-ups erupted twice in May, at Pangong lake, in Ladakh, and at Naku La in Sikkim, 1,200km to the east, resulting in serious injuries on both sides. In total, the PLA grabbed around 40 to 60 square kilometres of territory that India considers to be its own, estimates Lieutenant-General H.S. Panag, a former head of the Indian army’s northern command.

Even then, India’s government played down the severity of the crisis, eager to avoid giving the impression that it had been caught napping on the border—and mindful that a nationalist backlash would make it harder to defuse the situation. As diplomats and generals worked the phones and met at the border, things seemed to be calming. On June 9th India’s government said China had pulled back troops, tents and vehicles at the Galwan valley and another site (though not the lake), and that India had reciprocated. On June 13th General M.M. Naravane, India’s army chief, cheerfully declared that talks had been “very fruitful”.

The deadly clash two days later suggests they were clearly not fruitful enough. India’s army initially said that an officer and two soldiers had been killed “during the de-escalation process”, though army sources later privately acknowledged a far higher toll. The army added that “both sides suffered casualties”. Indian press reports suggest that the troops had been meeting to discuss the details of a withdrawal when a fight broke out, causing Indian soldiers to fall down a slope. “The Chinese seem to have brought iron rods, sticks studded with metal tips and stones,” says Nitin Gokhale, an Indian defence analyst. “The Indians also had some of their equipment.” Even 24 hours after the clash, an Indian major and captain were reported to be in Chinese custody.

China’s government was unrepentant. It said that India had gone back on earlier agreements and “twice crossed the border line for illegal activities and provoked and attacked Chinese personnel”. Hu Xijin, editor of the Global Times, a state-run tabloid, acknowledged the Chinese casualties in a tweet. If PLA soldiers were killed, these would be China’s first fatalities in combat, outside of peacekeeping, since skirmishes with Vietnam in the 1980s.

The immediate cause of the current crisis seems to have been India’s build-up of infrastructure in eastern Ladakh, including a key north-south road, making it easier to move troops and redressing China’s advantage in logistics. “What we’re seeing right now is the friction of both sides adjusting to a more capable and more resolved Indian approach to the LAC,” says Rohan Mukherjee of Yale-NUS College. But the two countries have also been carried to this point by wider geopolitical currents.

Though India and China have been rivals for a half-century—the PLA thumped India’s army in a brief border war in 1962—their rivalry has grown more intense over the past decade. The border has turned stormier, with Chinese incursions in Ladakh occurring in 2013 and 2014, and a 73-day stand-off on the edge of Bhutan in 2017. Last year China was irked by India's decision to revoke the constitutional autonomy of Jammu & Kashmir and carve out Ladakh into a separate territory, ruled directly from Delhi. Indian officials also ramped up rhetoric on retaking the entirety of the old princely state—including a sliver handed to China by Pakistan in 1963. India is anxious over China’s growing economic and political clout on India’s periphery—in Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka—and over the influx of Chinese warships into the Indian Ocean.

In response, successive Indian governments have tilted closer to America, with which India signed a $3.5bn arms deal in February, and China’s rivals in Asia, such as Vietnam. A quartet of China-sceptic countries known as the “Quad”, comprising America, Australia, India and Japan, now meet regularly. Though India is at pains to stress that the Quad is not an alliance, Australia may soon join naval exercises involving the other three countries, lending a naval dimension to the group.

The violent turn in the border dispute is likely to accelerate these trends. “We are at a worrisome and extremely serious turning-point in our relations with China,” says Nirupama Rao, a former head of India’s diplomatic service and ambassador to China. She notes a "clear asymmetry of power" between the two countries. India is likely to deepen its relationship with America and increase its defence budget, says Mr Mukherjee. As both sides shift resources to the border, “there will be a period of adjustment in which things may be especially heated,” he says.

Yet India now faces military and diplomatic turbulence with three of its neighbours. On June 12th an Indian citizen was killed by Nepalese border guards, amid a separate border row between India and Nepal. Relations with Pakistan are also fraught after an Indian soldier was killed by Pakistani firing in Kashmir on June 14th and, the next day, two Indian officials in Pakistan were allegedly abducted for more than ten hours and tortured by “Pakistani agencies”. And then more soldiers were sent tumbling to their deaths by China’s troops.

-An article first published on yesterday(16) in "The Economist"

---------------------------

by (2020-06-17 09:44:47)

Leave a Reply