-By: A Special Correspondent

(Lanka-e-News -12.July.2025, 11.10 PM) When the position of Basnayake Nilame—the lay custodian of a major Buddhist shrine—is up for election at Sri Lanka’s most sacred temple, the Temple of the Tooth (Sri Dalada Maligawa) in Kandy, one might expect reverence, dignity, and purity of purpose. What the public too often witnesses instead is a spectacle tainted by political interference, deep-pocketed manipulation, and behind-the-scenes bargaining with both officials and clergy.

The Basnayake Nilame may not hold the central administrative power that the Diyawadana Nilame does, but his role as custodian of the devalaya (temple or shrine) within the broader Dalada Maligawa complex is one of significant cultural and spiritual responsibility. The position, rooted in centuries of Buddhist tradition, demands integrity, discipline, and devotion. Yet in the murky lead-up to the selection process now underway, questions of corruption, patronage, and abuse of office loom large.

The official process appears orderly on paper. It is overseen by the Commissioner General of Buddhist Affairs, with key input from senior monks—the Mahanayaka Theras of Malwatta and Asgiriya Chapters—and select lay voters. It is meant to be a consensus-based, spiritually grounded decision-making process. However, insiders and critics warn that the system has become increasingly susceptible to the influence of money, power, and backroom deals.

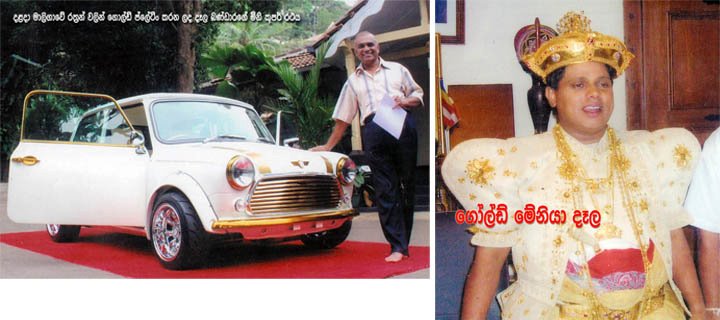

Recent reports suggest that some aspirants to the Basnayake Nilame role are spending lavishly—on unofficial “campaigning”, personal gifts, favours to officials, and even religious leaders—undermining the sanctity of the process. One candidate, for example, is alleged to have spent millions earned through unregulated gem mining operations in Nivithigala, Ratnapura—a region infamous for both its precious stones and its murky dealings.

Others reportedly come with dubious track records: casino owners, informal moneylenders, men with personal links to Thai sex workers and foreign gem merchants, former devalaya custodians whose previous tenures were marred by financial irregularities, and individuals backed by political machines and media influence. The involvement of figures linked to media networks such as “Vijaya Radio” raises further alarm about the convergence of spiritual office and commercial interests.

In any functioning democracy, especially one governed by a coalition promising anti-corruption and transparency—as Sri Lanka’s National People’s Power (NPP) government claims to be—such processes would be subject to independent scrutiny. And yet, there is no formal monitoring by Sri Lanka’s Bribery Commission, Financial Crimes Investigation Division (FCID), or the Auditor General’s Department.

This is not merely a moral crisis—it is a legal one. If financial inducements are being offered to voters, if government agents are being “looked after” in return for their silence, or if civil society is being deliberately excluded from observing the process, then this election becomes not just flawed but illegal.

The NPP government, which campaigned heavily on its promise to clean up state institutions, now faces its first major test in the religious domain. To remain credible, it must not allow religious appointments—especially those at the pinnacle of Buddhist religious heritage—to be treated like municipal tenders.

One straightforward solution lies in transparency. Allow independent monitors—lawyers, religious scholars, media observers, and civil society organisations—to observe the process. Let the public know what financial disclosures candidates are required to make. Have an audit mechanism that ensures campaign financing is not sourced from illegal industries such as unlicensed gem mining or moneylending.

In a country where public officials are required to submit asset declarations, why should Basnayake Nilames be exempt? These individuals are entrusted with managing millions in temple revenues, donations, and cultural property. Their financial dealings, especially during selection campaigns, should be subject to scrutiny.

And what of accountability? Former Nilames who are known to have siphoned funds or who maintain offshore accounts should not be eligible to contest, much less succeed, in these sacred roles. One cannot protect a shrine with hands stained by abuse of trust.

The most disquieting aspect of the current environment is the normalisation of patronage. It is whispered—sometimes openly spoken—that certain candidates are “buying” the position. Luxury vehicles have reportedly been promised to lay voters. Foreign holidays for officials’ families have been arranged, all off the books. Monks, too, are being courted—less for their blessings, more for their influence.

In an era where Sri Lanka is attempting to emerge from a crippling economic crisis, the idea that temple leadership roles can be bought with dirty money is not just morally repugnant—it is nationally self-destructive. The public’s faith in religion is deeply intertwined with its hope for a more ethical state. When that spiritual faith is exploited for personal gain, what remains?

The question now confronting Sri Lanka is whether it will finally treat the selection of temple custodians as the spiritual calling it claims to be, or allow it to slip further into the hands of those who see the temple as a money-spinner and a political badge of honour.

If reports of bribery, manipulation, and dubious candidates continue to mount, the NPP government must act. Investigators should be deployed. Financial records should be scrutinised. The selection should be postponed, if necessary, to preserve its legitimacy.

Above all, Sri Lanka must reaffirm that positions of religious significance cannot be for sale. Not to the rich. Not to the politically connected. Not to those who would gamble away the sanctity of the Temple of the Tooth for the price of a title.

If Sanga leaders, the Commissioner General of Buddhist Affairs, and the political leadership fail to ensure transparency now, they risk not only undermining the credibility of the temple but eroding the moral spine of the Buddhist establishment itself.

Role: The Basnayake Nilame is the lay (non-monastic) custodian responsible for the secular administration of a devalaya, typically associated with a deity or guardian figure within a Buddhist complex.

In the Temple of the Tooth: The position carries both ceremonial importance and real responsibility, especially in managing assets, festivals, and day-to-day logistics.

Selection Process: Overseen by the Department of Buddhist Affairs and senior monks, the process involves a closed-circle vote among designated stakeholders.

Controversies: Repeated allegations of political interference, misuse of temple funds, and vote-buying have surrounded recent elections.

Civil society groups and religious leaders who care for the preservation of Sri Lanka’s cultural and religious heritage must speak now—or risk losing these sacred spaces to ambition, corruption, and unchecked power.

-By: A Special Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-07-12 19:03:45)

Leave a Reply