-By LeN Parliamentary and Judicial Correspondent

(Lanka-e-News -26.Aug.2025, 9.50 PM) In the twilight of his long and controversial career, Ranil Wickremesinghe has come to embody the paradox of Sri Lankan politics: a statesman once hailed as the arch-technocrat, now reduced to a defendant in court, clinging to bail on medical grounds that sound more like a catalogue of human frailty than a clinical report.

The charge sheet against him is stark. Misappropriation of public funds. Abuse of office. A reckless expenditure of 16.6 million rupees — taxpayer money — on what prosecutors describe as nothing more than a two-day private jaunt overseas. At a time when the nation is bankrupt, creditors are circling, and citizens are told to tighten their belts, Wickremesinghe allegedly treated the Treasury like a family wallet.

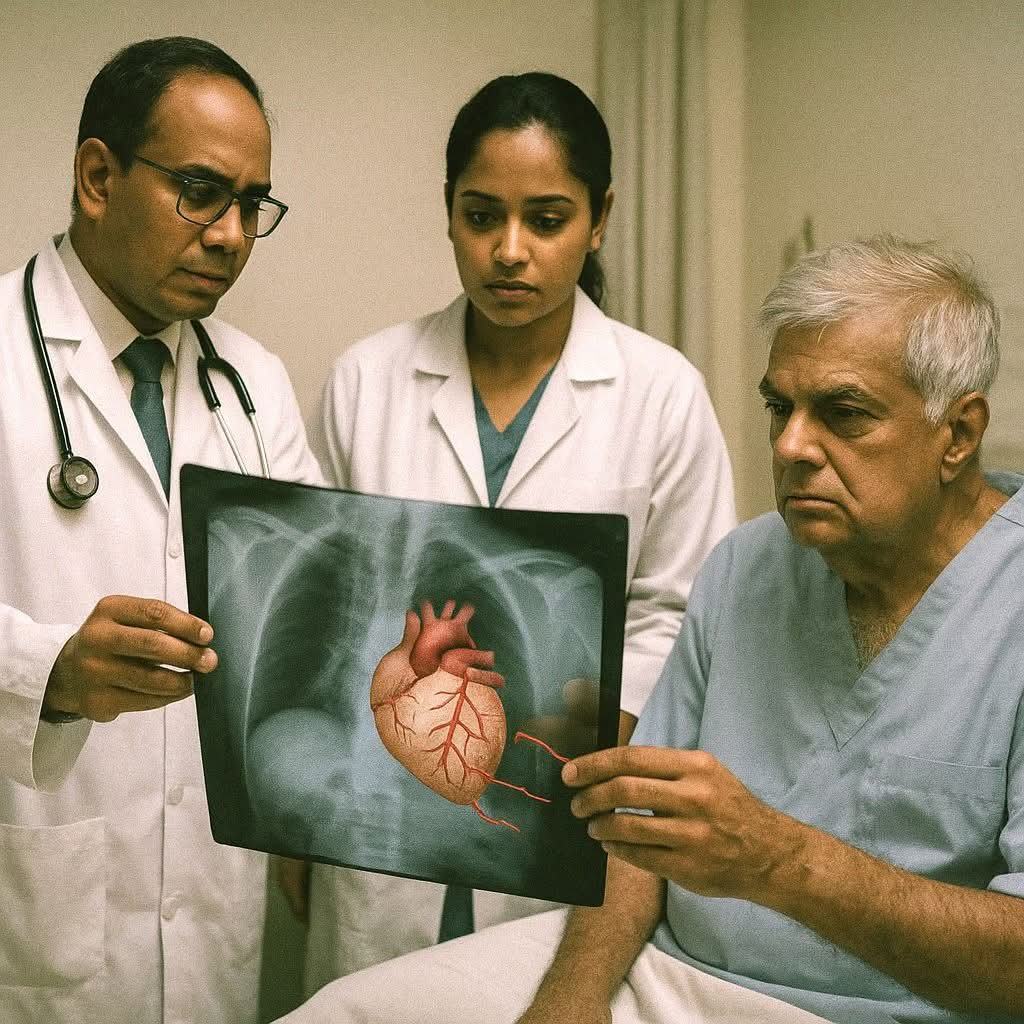

But it is not just the accusations of corruption that have transfixed the nation. It is the extraordinary spectacle that unfolded in court: the former President portrayed by his defence counsel as a man so riddled with illness that he is little more than a “walking catastrophe” — or, as his lawyer Anuja Premaratne put it in Sinhala, “an ambulatory coffin.”

The proceedings at Colombo’s Magistrate Court had all the theatre of a Shakespearean trial, part tragedy, part farce. Defence lawyers produced medical reports that listed Wickremesinghe’s ailments with dizzying detail. Among the catalogue:

Necrosis of the heart muscle.

Blockage in three out of four coronary arteries.

Kidney disease.

Dangerous levels of diabetes.

Pancreatic infection.

Abnormally low sodium levels.

Hypertension so severe it could trigger cardiac arrest at any moment.

Lung infection.

Critically weakened immune system.

Sleep apnoea, with episodes of suffocation lasting up to three minutes at night.

It was the sort of medical narrative that would render most men bedridden, if not buried. Premaratne told the bench bluntly: “Your Honour, my client suffers from every malady that could possibly afflict a human body. His life is in grave danger.”

The irony, of course, was not lost on the courtroom. If Wickremesinghe is indeed the medical wreck described, then how — prosecutors asked — did he so recently petition the court for permission to fly to India for a political gathering?

Dileepa Peiris, the Additional Solicitor General, was quick to skewer the defence. His rebuttal was merciless.

“My Lady,” he told Magistrate Nilupuli Lankapura, “we are asked to believe that the accused suffers from no fewer than ninety different ailments. And yet, in the last hearing, this very man sought leave to travel abroad. Is he dying, or is he flying?”

The prosecution went further, casting doubt not only on Wickremesinghe’s health claims but also on the authenticity of the invitation letter he submitted to justify his foreign excursion.

The court had earlier ordered the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) to probe the supposed letter from the University of Wolverhampton inviting Wickremesinghe’s wife for an honorary ceremony — an invitation that Wickremesinghe claimed necessitated his presence in Britain in September 2023.

The CID’s findings were damning: the letter was a fake. Neither the Sri Lankan High Commission in London, nor the Presidential Secretariat in Colombo, nor Wickremesinghe’s own long-serving private secretary Sandra Perera had any record of it. Even the phrasing of Wickremesinghe’s explanations contradicted themselves: first “private visit,” then “official visit,” then back again.

Peiris summed it up with prosecutorial precision: “This is not a clerical error. This is a fabricated document. It is a lie, presented to mislead this Honourable Court.”

Yet the forged invitation was only one strand of the case. The larger question — and the one that has gripped a country weary of impunity — is the expenditure of public funds.

The prosecution pointed out that Wickremesinghe’s dubious private trip cost the state 16.6 million rupees, more than three times the amount spent on his official presidential visit to Cuba, which had cost a relatively modest 5 million rupees.

“This,” declared Peiris, “is not mere misuse of funds. It is outright plunder — a cannibalisation of the people’s money.”

In a country where pensioners queue for medicine, schools lack textbooks, and electricity bills soar, the optics of such extravagance have proved politically lethal.

The Proceeds of Public Property Act — a statute designed precisely to prevent public officials from misusing state assets — normally bars bail until trial is concluded. Yet in this instance, Wickremesinghe’s lawyers leaned heavily on his supposed medical fragility.

Magistrate Lankapura, weighing stacks of medical reports from both private hospitals and a panel of six senior consultants at Colombo National Hospital, concluded that while she could not independently verify the truth of every diagnosis, the documents bore professional signatures and therefore carried credibility.

On that basis, she ruled that Wickremesinghe should be released on bail: three sureties of 5 million rupees each. He is, technically, a free man again — though tethered to ongoing judicial oversight.

“The court accepts that the accused requires close medical supervision,” Lankapura pronounced, “and therefore grants conditional bail.” The next hearing is fixed for October 29.

But here lies the rub. In Sri Lanka, the theatre of illness is as much a part of political culture as campaign rallies and patronage. The pattern is familiar: powerful men enter court in wheelchairs, their faces pale, their bodies draped in medical paraphernalia. They emerge, once granted bail, miraculously rejuvenated — walking unaided, illness forgotten, the very picture of robust health.

Many in Colombo now ask: will Wickremesinghe prove the latest in this long line of medical resurrections?

For all the talk of necrotic heart tissue and blocked arteries, the former President has shown little sign in public life of incapacitation. His condition, if genuine, should have necessitated angioplasty and immediate stenting long ago. Yet he remained politically active until his arrest, convening meetings, plotting strategies, and lobbying allies.

As one wag put it outside the courthouse: “In remand, he is a dying man. On bail, he will be a marathon runner.”

The case has inevitably drawn political theatre. Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa made a conspicuous visit to the hospital to see Wickremesinghe, emerging to tell reporters that his old rival was “resting comfortably.” The subtext was clear: even in disgrace, Wickremesinghe remains a node in the complex web of Sri Lankan elite politics.

The opposition, meanwhile, has rallied half-heartedly to his side, though the turnout in Colombo yesterday was pitiful by comparison with the great Aragalaya protests of 2022. Where hundreds of thousands once filled Galle Face, only a few hundred turned up, most of them hangers-on of minor opposition MPs like Mujibur Rahman.

And their conduct did little to inspire public sympathy. In one incident, a supporter hurled a bottle at a policeman, breaking his nose — a contrast to the Aragalaya movement, where protesters famously handed roses to police rather than stones.

The comparison was not lost on Colombo’s citizenry. As one observer remarked, “Ranil’s crowds bring bottles; the youth brought flowers.”

For Wickremesinghe and his loyalists, the bail decision is a lifeline. The very fact that his illnesses were “discovered” only after his remand has raised eyebrows. As critics noted, necrotic heart tissue and triple artery blockage do not emerge overnight. These are long-standing conditions.

And yet, none of it had ever been raised before. Only once the prison gates closed did the ailments surface. “A convenient sickness,” muttered one lawyer outside the court, “diagnosed by remand.”

It is this coincidence that has fuelled suspicion that Wickremesinghe, his family, and his political machine now owe an unspoken debt to Magistrate Lankapura.

The legal case is far from over. The forgery allegation surrounding the Wolverhampton letter has already damaged Wickremesinghe’s credibility, and the spending of public funds is well-documented. If convicted under the Public Property Act, he could face a long custodial sentence.

Yet Sri Lankan politics is nothing if not elastic. Yesterday’s accused can become tomorrow’s ally, and today’s “ambulatory coffin” can re-emerge as tomorrow’s kingmaker.

For now, Wickremesinghe remains under medical supervision, at least officially. Whether he continues treatment at Colombo National Hospital, transfers quietly to a private clinic, or stages a Lazarus-like recovery to stride once more onto the political stage is anyone’s guess.

What is certain is that the case has struck a chord with the public. For a nation long accustomed to impunity among its elite, the sight of a former President facing remand was a Rubicon moment.

Whether it leads to genuine accountability — or merely another chapter in Sri Lanka’s long saga of selective justice — will depend on the resolve of the courts and the scrutiny of the public.

Until then, Wickremesinghe remains the man described by his own lawyer: a “walking coffin.” But in Sri Lankan politics, coffins often walk a long way.

-By LeN Parliamentary and Judicial Correspondent

---------------------------

by (2025-08-26 16:25:50)

Leave a Reply